You are about to embark on a journey into the intricate workings of your own biological defense system, a system constantly monitoring your environment for potential dangers and orchestrating your responses. This exploration will dissect the mechanisms through which your nervous system interprets and regulates perceived threats, offering insights into how these processes profoundly shape your experiences, behaviors, and overall well-being.

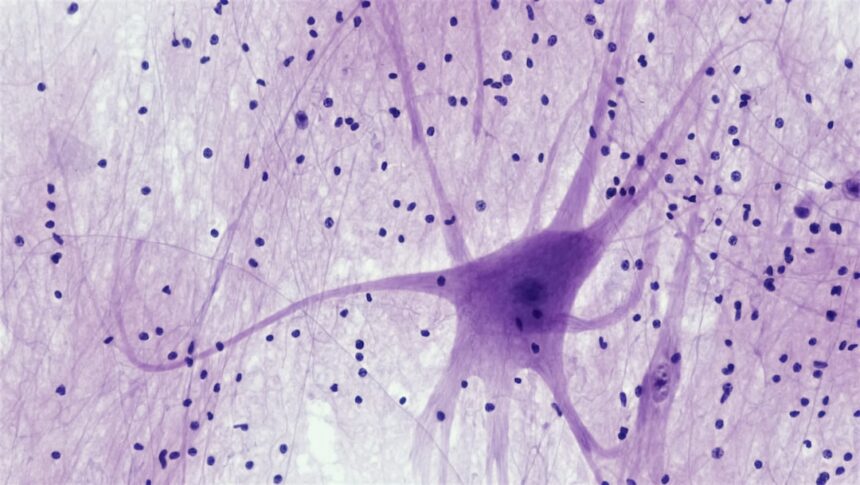

Your autonomic nervous system (ANS) operates largely outside your conscious control, continually making adjustments to maintain homeostasis. It is the silent superintendent of your internal environment, governing functions like heart rate, digestion, respiration, and sexual arousal. Within this system, two principal branches execute largely opposing but complementary roles in threat regulation.

Sympathetic Nervous System: The Accelerator

Consider your sympathetic nervous system (SNS) as the accelerator pedal of your internal environment. Its primary function is to prepare your body for immediate action – often referred to as the “fight, flight, or freeze” response. When activated, it instigates a cascade of physiological changes designed to maximize your chances of survival in the face of perceived danger.

- Physiological Manifestations: You might observe your heart rate increasing significantly as your body attempts to pump oxygenated blood more rapidly to your muscles. Your pupils dilate, allowing more light to enter your eyes, enhancing your visual perception of your surroundings. Digestion might cease or slow down dramatically as blood flow is diverted from non-essential functions to systems critical for immediate survival. Your breathing deepens and quickens, increasing oxygen intake.

- Neurochemical Release: This activation is largely mediated by the release of catecholamines, primarily adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine), from your adrenal glands and sympathetic nerve endings. These neurochemicals act as messengers, propagating the sympathetic signal throughout your body.

- Energy Mobilization: Your body mobilizes stored glucose, making it readily available for muscle contraction. This surge of energy provides the fuel for a rapid, powerful response.

Parasympathetic Nervous System: The Brake

In contrast to the SNS, your parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) acts as the brake, or the “rest and digest” system. Its primary role is to calm your body down after a threat has passed, or to maintain a state of equilibrium in the absence of perceived danger. It facilitates recovery, conserves energy, and promotes anabolic processes.

- Physiological Manifestations: You would notice your heart rate slowing down, your breathing becoming more regular and shallow, and your pupils constricting. Digestion resumes its normal processes, and blood flow returns to internal organs. Muscle tension decreases.

- Neurochemical Action: The primary neurotransmitter associated with the PNS is acetylcholine. It acts to slow heart rate, constrict pupils, and stimulate digestive processes.

- Energy Conservation: The PNS promotes the storage of energy and plays a crucial role in repairing and rebuilding tissues, restoring your body to its baseline state.

In exploring the intricate mechanisms of nervous system threat regulation, a related article that delves deeper into this topic can be found on Unplugged Psych. This resource provides valuable insights into how our nervous system responds to perceived threats and the implications for mental health. For further reading, you can access the article here: Unplugged Psych.

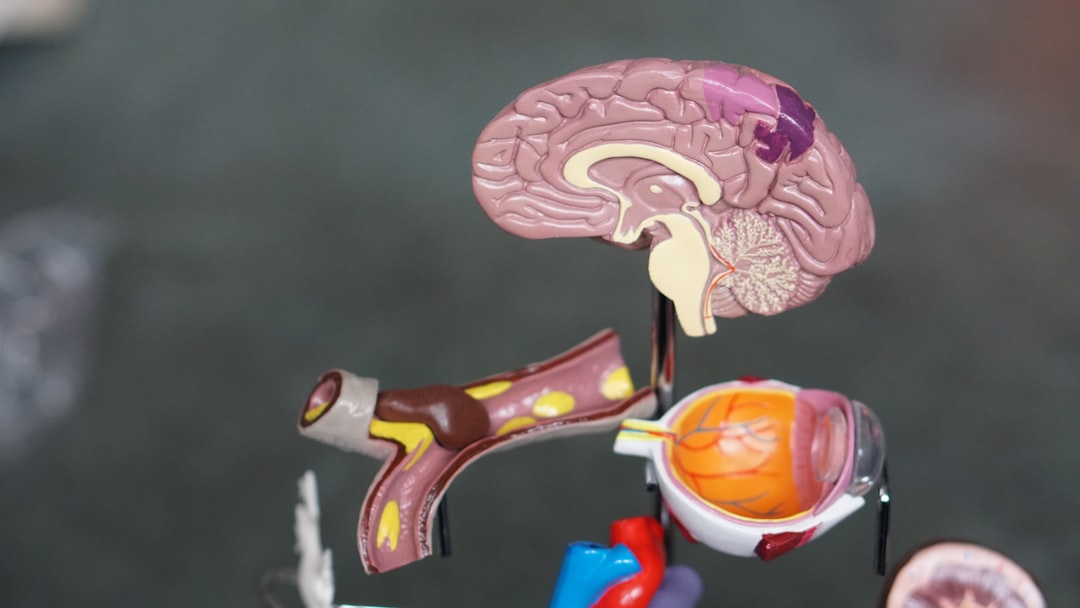

The Triune Brain Model and Threat Perception

Your brain, a marvel of evolutionary engineering, is often conceptualized as having a layered structure, reflecting its development over millions of years. This “triune brain model,” while a simplification, offers a useful framework for understanding how different brain regions contribute to threat perception and regulation.

The Reptilian Brain (Brainstem and Cerebellum)

At the core of your brain lies the “reptilian brain,” the oldest and most fundamental part. This region, encompassing the brainstem and cerebellum, is responsible for basic survival functions and instinctual behaviors.

- Automatic Regulation: It governs vital functions like breathing, heart rate, and body temperature. In the context of threat, it initiates primal, automatic responses, often pre-conscious, such as freezing or startling.

- Fundamental Survival: This part of your brain ensures your core physiological processes continue uninterrupted, even in the face of extreme stress.

The Mammalian Brain (Limbic System)

Surrounding the reptilian brain is the “mammalian brain,” primarily the limbic system. This region is home to your emotions, memories, and motivation. It plays a critical role in processing emotionally salient information, including threats.

- The Amygdala: The Alarm Bell: Within the limbic system, your amygdala acts as the primary alarm bell. It rapidly scans your environment for signs of danger, even before conscious recognition. Upon detecting a potential threat, it triggers a rapid cascade of physiological responses via its connections to the hypothalamus and brainstem.

- The Hippocampus: Contextual Memory: Your hippocampus is crucial for forming and retrieving memories, particularly those linked to context. It helps you differentiate between genuinely dangerous situations and those that merely resemble past threats. A malfunctioning hippocampus might lead to inappropriate threat responses in safe environments.

- The Hypothalamus: The Command Center: The hypothalamus is a small but powerful region that acts as the command center for your autonomic nervous system and endocrine system. It translates emotional signals from the amygdala into physiological responses, initiating the stress hormone cascade.

The Neocortex (Prefrontal Cortex)

The outermost and most recently evolved layer of your brain is the neocortex, particularly the prefrontal cortex (PFC). This region is responsible for higher-order cognitive functions such as planning, decision-making, rational thought, and impulse control.

- Executive Regulation: Your PFC plays a crucial role in regulating your threat responses. It can override or modulate the amygdala’s alarm signals, allowing you to assess situations more rationally and choose more adaptive responses.

- Conscious Appraisal: When faced with a potential threat, your PFC analyzes the situation, drawing upon past experiences and current context to determine the appropriate course of action. This allows you to differentiate between a truly menacing growl and a playful bark.

- Cognitive Reappraisal: Through cognitive reappraisal, your PFC can reframe a perceived threat, reducing its emotional impact. For example, if you interpret a nervous stomach as excitement for a presentation rather than anxiety, your physiological response will be different.

The Polyvagal Theory: Beyond Fight or Flight

Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory offers a more nuanced understanding of your autonomic nervous system, extending beyond the simplistic “sympathetic fight/flight, parasympathetic rest/digest” dichotomy. It proposes that your vagus nerve, a major component of the PNS, has distinct branches that mediate different physiological and behavioral states.

Dorsal Vagal Complex: Immobilization and Shutdown

The dorsal vagal complex (DVC) is phylogenetically older and primarily associated with immobilization behaviors. When sensing extreme or inescapable threat, your body might engage this system, leading to a state of learned helplessness, dissociation, or “feigned death.”

- Primitive Defense: This is a primal defense mechanism, a last resort when fight or flight are not viable options. Imagine an animal playing dead to avoid a predator.

- Physiological Profile: In this state, your heart rate might plummet, respiration could become shallow and irregular, and you might experience a sense of numbness or detachment. This can manifest as fainting, disassociation, or a feeling of being “frozen” in terror.

- Energy Conservation (Extreme): While seemingly maladaptive, this extreme response also conserves energy, potentially enhancing survival if the threat eventually dissipates.

Ventral Vagal Complex: Social Engagement and Safety

The ventral vagal complex (VVC) is the most recently evolved branch of the vagus nerve and is uniquely human. It is associated with social engagement, feelings of safety, and emotional regulation.

- Social Connection: The VVC is responsible for regulating your facial expressions, vocal tone, and head movements, facilitating social interaction and connection. When activated, you are more likely to engage with others, seek comfort, and feel safe.

- “Safe and Sound” State: When your VVC is active, your body is in a state of optimal physiological arousal, conducive to learning, growth, and relaxation. You feel grounded and connected.

- Co-Regulation: Through social interaction and prosocial behaviors, your VVC can co-regulate with another person’s VVC, helping both individuals feel safer and more regulated. This is why a comforting voice or a gentle touch can have such a profound calming effect.

The Neurobiology of Trauma and Chronic Stress

Your nervous system’s threat regulation mechanisms are designed to protect you from acute danger. However, prolonged exposure to stress or single traumatic events can dysregulate these systems, leading to a range of challenges.

Allostatic Load: The Wear and Tear

Chronic stress or repeated activation of your SNS without adequate periods of PNS recovery leads to “allostatic load.” This is the cumulative wear and tear on your body and brain resulting from prolonged or repeated stress responses.

- Physiological Consequences: Elevated cortisol levels, inflammation, cardiovascular strain, and impaired immune function are common consequences of persistent allostatic load.

- Cognitive Impairment: Chronic stress can impair your cognitive functions, including memory, attention, and decision-making, particularly impacting your prefrontal cortex.

- Emotional Dysregulation: You might find yourself more prone to anxiety, irritability, and depression, as your emotional regulation systems become overwhelmed.

Trauma and Nervous System Dysregulation

Trauma, defined as an event or series of events that overwhelms your ability to cope, often leaves a lasting imprint on your nervous system. Your brain, in an attempt to protect you, may remain in a hypervigilant state, misinterpreting benign cues as threats.

- Hyperarousal: You might experience persistent hyperarousal, characterized by exaggerated startle responses, difficulty sleeping, and chronic anxiety. Your SNS might be chronically activated, making it difficult to relax.

- Hypoarousal/Dissociation: Conversely, some individuals might experience hypoarousal or dissociation, where the dorsal vagal complex becomes the dominant response. This can manifest as emotional numbness, detachment, or a feeling of unreality.

- Triggering: Trauma survivors often experience “triggers,” sensory inputs (sights, sounds, smells) that unconsciously activate their fight/flight/freeze responses, even in safe environments. Your limbic system, particularly the amygdala, misinterprets these triggers as current threats, bypassing conscious rational thought.

Understanding how the nervous system regulates threats is crucial for comprehending our responses to stress and anxiety. A related article that delves deeper into this topic can be found at Unplugged Psych, where the mechanisms of threat perception and the body’s physiological responses are explored in detail. This resource provides valuable insights into the interplay between our nervous system and emotional regulation, highlighting the importance of managing stress for overall well-being.

Strategies for Nervous System Regulation

| Metric | Description | Typical Range/Value | Relevance to Threat Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate Variability (HRV) | Variation in time intervals between heartbeats | 40-100 ms (higher is better) | Indicator of parasympathetic nervous system activity; higher HRV suggests better threat regulation and stress resilience |

| Sympathetic Nervous System Activation | Level of fight-or-flight response activation | Measured via norepinephrine levels or skin conductance | Increased activation signals heightened threat perception and stress response |

| Parasympathetic Nervous System Activation | Level of rest-and-digest response activation | Measured via vagal tone or acetylcholine levels | Higher activation supports calming and threat regulation |

| Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis Activity | Cortisol secretion levels in response to stress | Normal cortisol: 6-23 mcg/dL (morning) | Regulates stress response; dysregulation can impair threat regulation |

| Amygdala Reactivity | Neural response to perceived threats | Measured via fMRI BOLD signal intensity | Higher reactivity correlates with increased threat sensitivity |

| Prefrontal Cortex Activity | Executive control over emotional responses | Measured via fMRI or EEG | Greater activity supports regulation and inhibition of threat responses |

Understanding how your nervous system regulates threats empowers you to actively engage in practices that promote balance and resilience. While professional help is essential for significant trauma, several strategies can support your nervous system’s health.

Cultivating Mind-Body Awareness

Developing a keen awareness of your bodily sensations is a fundamental step in nervous system regulation. You are learning to read the language of your own internal landscape.

- Interoception: Practices like mindfulness and meditation enhance interoception, your ability to perceive the internal state of your body. This allows you to recognize early signs of sympathetic activation (e.g., shallow breathing, muscle tension) or dorsal vagal shutdown (e.g., numbness, detachment).

- Body Scans: Regularly engaging in body scan meditations, where you systematically bring attention to different parts of your body, can help you identify areas of tension or deregulation.

Engaging the Ventral Vagal Complex

Actively stimulating your ventral vagal complex can promote feelings of safety, connection, and calm.

- Social Connection: Nurturing healthy relationships and engaging in prosocial activities (e.g., volunteering, active listening) directly activates your VVC. Eye contact, a warm tone of voice, and gentle touch can all facilitate this.

- Prosodic Vocalization: Singing, humming, chanting, and even talking in a soothing tone can stimulate the vagus nerve. The vibrations produced resonate with the vagus nerve, promoting relaxation.

- Mindful Breathing: Slow, deep, diaphragmatic breathing, particularly with an extended exhale, is a powerful way to activate your PNS and calm your nervous system. This signals to your brain that you are safe.

Modulating Sympathetic Activation

While sympathetic activation is vital for survival, chronic activation is detrimental. Learning to consciously downregulate your stress response is crucial.

- Physical Activity: Regular physical exercise, especially activities that allow for the physical expression of energy (e.g., running, dancing), can help release accumulated stress hormones and facilitate the return to a calmer state.

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation: This technique involves systematically tensing and then relaxing different muscle groups, helping you become aware of and release physical tension.

- Time in Nature: Spending time in natural environments has been shown to reduce stress hormones and promote relaxation, allowing your nervous system to downregulate.

By understanding the intricate dance between your sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, and the roles your different brain regions play in threat assessment, you gain a powerful lens through which to view your own experiences. This knowledge empowers you to not only navigate the challenges of stress and trauma but also to cultivate a more resilient, regulated, and ultimately, more fulfilling life. You are not a passive recipient of your nervous system’s dictates; you are an active participant in its regulation.

WARNING: Your Empathy Is a Biological Glitch (And They Know It)

FAQs

What is the nervous system’s role in threat regulation?

The nervous system detects and processes potential threats through sensory input and activates appropriate responses to ensure survival. It regulates physiological and behavioral reactions to perceived danger, such as the fight, flight, or freeze responses.

Which parts of the nervous system are involved in threat regulation?

Key components include the amygdala, hypothalamus, and brainstem, which coordinate the detection of threats and initiate stress responses. The autonomic nervous system, particularly the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches, modulates bodily reactions to threats.

How does the nervous system differentiate between real and perceived threats?

The brain evaluates sensory information and past experiences to assess the level of danger. While the amygdala rapidly processes potential threats, higher brain regions like the prefrontal cortex help interpret context and regulate emotional responses to avoid overreacting to non-threatening stimuli.

What happens during the fight, flight, or freeze response?

When a threat is detected, the sympathetic nervous system activates, increasing heart rate, blood pressure, and energy availability. This prepares the body to confront or escape the danger. In some cases, the freeze response occurs, causing temporary immobility as a survival strategy.

Can threat regulation be improved or trained?

Yes, practices such as mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and stress management techniques can help regulate the nervous system’s response to threats. These methods enhance emotional regulation and reduce excessive or chronic stress reactions.