You are about to embark on an exploration of one of the brain’s most intricate and fundamental defense mechanisms: dissociation. This phenomenon, often misunderstood and stigmatized, represents a spectrum of responses your brain employs to cope with overwhelming experiences. Far from being a mere psychological quirk, dissociation is deeply rooted in your neurobiology, sculpted by evolution to ensure your survival in the face of perceived threats. As you delve into this topic, you will gain a profound appreciation for your brain’s adaptive capacity, even when those adaptations manifest in ways that are ultimately distressing.

Your brain is a master of adaptation, and its primary directive is your survival. To understand dissociative defense responses, you must first acknowledge their evolutionary origins. Imagine your ancient ancestors facing a true life-or-death situation – a predatory attack or an inescapable environmental catastrophe. In such extreme scenarios, a purely fight-or-flight response might be futile or even counterproductive. Your body, in its wisdom, developed alternative strategies to minimize harm and maximize the chances of survival, even if it meant sacrificing immediate conscious awareness and emotional processing.

The “Playing Dead” Instinct

Think of the opossum, a creature famous for its ability to feign death. This isn’t merely a conscious choice; it’s an autonomic response designed to deter predators. Your brain possesses a similar, albeit far more sophisticated, mechanism. When faced with an inescapable threat that triggers overwhelming fear, pain, or helplessness, your neurobiological systems can initiate a “freeze” response, which can escalate into various forms of dissociation. This isn’t a sign of weakness; it’s a testament to your hardwired survival instincts. You are, in essence, biologically programmed to “play dead” internally when external options are exhausted.

Dissociation as a Primitive Anesthetic

Consider the scenario of a severe injury in a pre-modern context, where medical intervention was non-existent. The excruciating pain could be debilitating, hindering escape or further survival efforts. In such circumstances, your brain can act as its own anesthetic, dampening sensory input and emotional processing. This isn’t an intentional act on your part; it’s an automatic neurochemical cascade designed to reduce suffering and allow for potential escape or endurance. This primitive analgesic function is a cornerstone of dissociative processes, allowing you to bypass unbearable sensations.

The neurobiology of dissociative defense responses is a fascinating area of study that explores how the brain reacts to trauma and stress. For a deeper understanding of this topic, you can refer to the article found at Unplugged Psych, which discusses the mechanisms behind dissociation and its implications for mental health. This resource provides valuable insights into how these responses are linked to brain function and emotional regulation.

Neurobiological Underpinnings of Dissociation

To truly grasp how dissociation works, you must peer into the intricate workings of your brain. Modern neuroscience, through advancements in neuroimaging and neurochemical research, has begun to unravel the complex neural circuitry involved in dissociative states. It’s not a single region or pathway, but rather a dynamic interplay of various brain systems.

The Default Mode Network (DMN) and Its Role

The Default Mode Network (DMN) is a collection of brain regions that are active when your mind is not focused on the external world, such as during daydreaming, mind-wandering, or self-reflection. In dissociative states, particularly depersonalization and derealization, research suggests that there can be altered connectivity within the DMN. You might experience a sense of detachment from your body or your surroundings – as if you are observing yourself or the world from a distance. This “observer” state could be linked to an overactive or dysregulated DMN, creating a separation between your conscious self and your ongoing experience.

The Amygdala and Fear Processing

The amygdala, a small almond-shaped structure deep within your temporal lobe, is the brain’s fear alarm. It is highly active when you encounter threats and plays a crucial role in initiating your fight-or-flight (and freeze) responses. In dissociative states, particularly those triggered by trauma, there can be a complex interplay between the amygdala and other brain regions. While the amygdala might be hyperactive in signaling danger, other regions, such as the prefrontal cortex, might struggle to regulate this fear response effectively. You might experience an overwhelming sense of dread or terror, yet simultaneously feel removed from that emotion, as if it’s happening to someone else. This paradoxical emotional experience is a hallmark of certain dissociative phenomena.

The Prefrontal Cortex and Executive Function

Your prefrontal cortex (PFC), located at the front of your brain, is responsible for executive functions such as planning, decision-making, working memory, and emotional regulation. In healthy stress responses, your PFC helps you to appraise threats, formulate strategies, and manage your emotional reactions. However, under extreme duress, the PFC can become dysregulated, leading to a diminished capacity for these executive functions. This can contribute to the feeling of being “on autopilot” during dissociative episodes, where your ability to consciously control your thoughts, feelings, and actions is compromised. You might find yourself unable to articulate what is happening, or to make sense of the sensory input you are receiving.

The Hippocampus and Memory Formation

The hippocampus is vital for the formation of new memories and the retrieval of existing ones, particularly episodic memories – memories of specific events. When you experience trauma, and especially when dissociation is involved, your hippocampus can be significantly affected. This can lead to fragmented memories, amnesia for parts of the traumatic event, or a sense of derealization where the event feels unreal or dreamlike. Your brain, in an attempt to protect you from overwhelming emotional pain, might essentially “scramble” the memory encoding process, making it difficult to access or integrate the experience coherently. This is why individuals who have experienced severe trauma often struggle with clear and linear recall.

Different Forms of Dissociation and Their Neural Correlates

Dissociation is not a monolithic phenomenon. It manifests in various forms, each with distinct, though often overlapping, neurobiological signatures. Understanding these different expressions helps to demystify your experience and provides a framework for comprehending the varied impact of trauma and stress.

Depersonalization and Derealization

Depersonalization involves a feeling of detachment from your own body, thoughts, or emotions. You might feel as if you are an outside observer of your own life, or that your body actions are not your own. Derealization, on the other hand, involves a sense of unreality or detachment from your surroundings. The world may appear distorted, dreamlike, or artificial. Neurobiologically, both phenomena are linked to alterations in self-referential processing and sensory integration.

The Role of the Temporoparietal Junction (TPJ)

The temporoparietal junction (TPJ) is a critical brain region involved in self-other distinction and perspective-taking. Studies suggest that altered activity or connectivity in the TPJ could contribute to depersonalization, creating a disruption in your sense of self and ownership of your body. When this region is dysregulated, it can be like a switch flicking, suddenly making you feel as though you are observing your life from a third-person perspective, rather than experiencing it directly in the first person.

Aberrant Sensory Processing

In derealization, your brain appears to be actively distorting or filtering sensory information from your environment. This isn’t a problem with your eyes or ears, but rather with how your brain interprets and processes that input. You might find familiar objects or places seem unfamiliar, two-dimensional, or devoid of emotional resonance. This could involve dysregulation in areas responsible for integrating sensory input with emotional salience, such as the insula. Your brain might be creating a buffer, literally making the world seem less real to protect you from its perceived threat.

Dissociative Amnesia

Dissociative amnesia involves an inability to recall important personal information, usually of a traumatic or stressful nature, that is too extensive to be explained by ordinary forgetfulness. This can manifest as localized amnesia (inability to recall a specific event), selective amnesia (inability to recall only certain aspects of an event), or generalized amnesia (loss of identity and life history).

The Shut-Down Response

From a neurobiological perspective, dissociative amnesia is often linked to an active “shut-down” of memory encoding and retrieval processes during overwhelming events. This can involve the downregulation of the hippocampus’s activity, effectively preventing the formation of coherent narrative memories. Imagine your brain hitting a pause button on recording during a particularly distressing moment; this isn’t a conscious choice, but an automatic neurochemical response designed to protect you from the full emotional impact of the experience.

State-Dependent Memory

Another aspect of dissociative amnesia is state-dependent memory. Information encoded during a highly stressful or dissociative state may only be accessible when you are in a similar physiological or emotional state. This is why memories might spontaneously resurface, seemingly out of nowhere, when you encounter triggers that mimic the original traumatic context. Your brain has filed these memories away in a very specific context, making them difficult to retrieve outside of that same “state.”

The Neurochemistry of Dissociation

Beyond brain structures and networks, neurotransmitters – the chemical messengers of your brain – play a crucial role in mediating dissociative responses. These chemicals influence your mood, perception, cognition, and overall physiological state.

The Opioid System

Your brain naturally produces opioid peptides, such as endorphins, which act as natural pain relievers and can induce feelings of euphoria or detachment. In situations of extreme stress or pain, your endogenous opioid system can become highly active, leading to analgesia (pain relief) and a sense of emotional numbness or unreality. This is your brain’s natural “morphine drip,” deployed to alleviate overwhelming suffering during traumatic events. You might feel a strange calm or a lack of emotional response during an otherwise terrifying experience, and this could be due to a surge in these natural opioids.

Norepinephrine and Adrenaline

Norepinephrine and adrenaline are catecholamines that are central to your body’s stress response. They increase heart rate, blood pressure, and alertness. While high levels of these neurotransmitters typically characterize fight-or-flight, in some dissociative states, there can be a paradoxical increase in these alongside a sense of emotional detachment. This can lead to a feeling of hyperarousal without emotional connection, a state of being “amped up” but emotionally numb. Your body is physically reacting to danger, but your mind is attempting to disengage from the overwhelming emotional data.

GABA and Glutamate Imbalance

GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in your brain, while glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter. During stress and trauma, the delicate balance between these two can be disrupted. An overactivity of glutamate can lead to excitotoxicity and neuronal damage, while an increase in GABA can contribute to the “shut-down” or anesthetic effects observed in dissociation. This imbalance can contribute to the cognitive fog and derealization often experienced during dissociative episodes, impacting clarity of thought and perception.

Recent research into the neurobiology of dissociative defense responses has shed light on how the brain processes trauma and stress. A fascinating article discusses the intricate mechanisms involved in these responses and their implications for mental health treatment. For those interested in exploring this topic further, you can read more about it in the article here. Understanding these neurobiological processes is crucial for developing effective therapeutic interventions for individuals who experience dissociation as a coping mechanism.

Therapeutic Implications and Recovery

| Metric | Description | Neurobiological Correlate | Typical Measurement Method | Relevant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate Variability (HRV) | Variation in time interval between heartbeats during dissociative states | Autonomic nervous system regulation, especially parasympathetic activity | Electrocardiogram (ECG) | Reduced HRV observed during acute dissociative defense responses indicating autonomic dysregulation |

| Prefrontal Cortex Activity | Engagement of executive control and emotional regulation during dissociation | Medial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | Functional MRI (fMRI), PET scans | Increased prefrontal activity linked to suppression of limbic responses during dissociation |

| Amygdala Reactivity | Emotional processing and threat detection during dissociative defense | Amygdala | fMRI, PET | Decreased amygdala activation observed in dissociative states, suggesting emotional numbing |

| Electroencephalogram (EEG) Patterns | Brainwave activity changes during dissociative episodes | Various cortical regions | EEG recording | Increased theta and delta power associated with dissociative absorption and detachment |

| Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis Activity | Stress hormone regulation during dissociative defense | Hypothalamus, pituitary gland, adrenal cortex | Cortisol levels in saliva or blood | Altered cortisol responses indicating blunted or exaggerated stress response in dissociative individuals |

| Default Mode Network (DMN) Connectivity | Brain network involved in self-referential thought and consciousness | Medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus | Resting-state fMRI | Disrupted DMN connectivity correlates with dissociative symptoms and altered self-awareness |

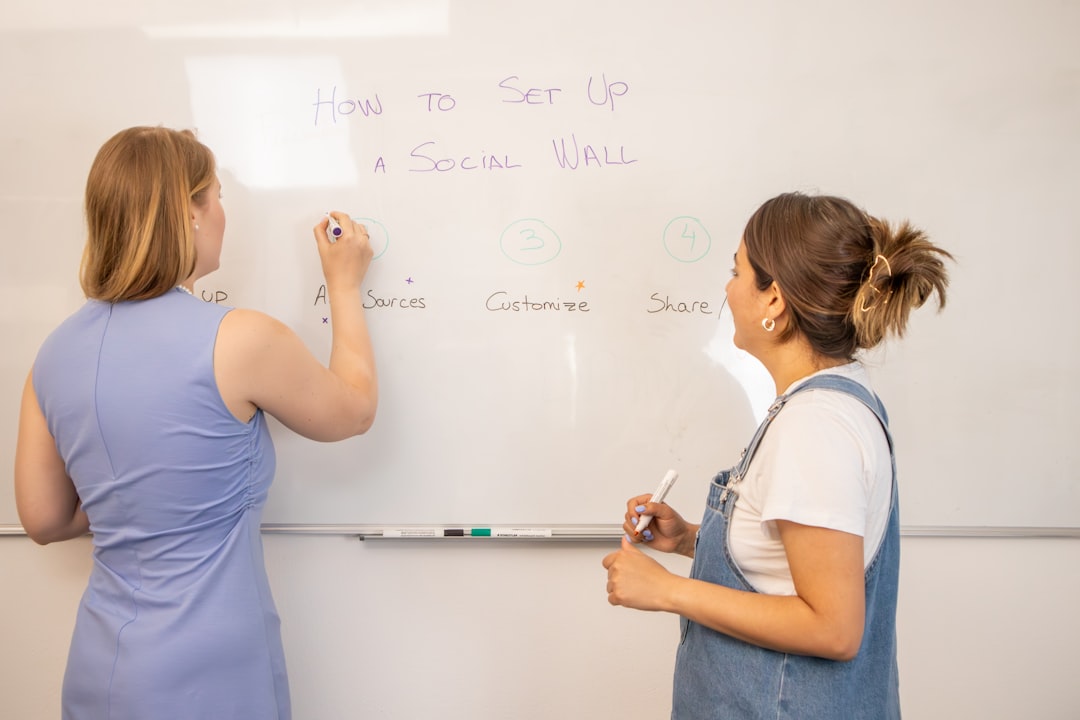

Understanding the neurobiology of dissociative defense responses is not merely an academic exercise; it has profound implications for treatment and recovery. If you or someone you know experiences dissociative symptoms, recognizing their biological basis can help to destigmatize the experience and guide effective interventions.

Neuroplasticity and Healing

Your brain is remarkably plastic, meaning it can change and adapt throughout your life. Even after experiencing trauma and developing dissociative patterns, your brain retains the capacity to heal and rewire itself. Therapeutic approaches, particularly those that focus on emotional regulation, somatic experiencing, and trauma processing, aim to help you re-integrate fragmented experiences and establish healthier coping mechanisms. This involves guiding your brain to form new neural pathways that support resilience and a more coherent sense of self. It’s like rerouting traffic around a damaged bridge, allowing for smoother and more efficient movement.

Somatic and Top-Down Approaches

Effective treatments often combine “bottom-up” (somatic) and “top-down” (cognitive) approaches. Somatic therapies focus on your bodily sensations and aim to help regulate your autonomic nervous system, which is often dysregulated in dissociative states. Top-down approaches, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), help you to identify and challenge unhelpful thought patterns and develop new coping skills. By addressing both your body’s physiological responses and your cognitive processing, you can begin to heal the neural circuitry underlying dissociative defenses.

The Importance of Safe Relationships

Crucially, safe and consistent therapeutic relationships play a vital role in recovery. Your brain’s capacity for trust and attachment is fundamental to healing. A therapist who provides a secure base and attunes to your experience can help to regulate your nervous system and facilitate the processing of traumatic memories that may have been “frozen” in a dissociative state. This relational safety helps to modulate your amygdala’s threat responses and promotes the activation of your prefrontal cortex, allowing for more adaptive emotional processing.

In conclusion, your brain’s capacity for dissociative defense responses is a testament to its astounding evolutionary sophistication. While often distressing and disruptive, these mechanisms are deeply rooted in your neurobiology, designed for your protection in the face of overwhelming threat. By understanding the intricate interplay of brain regions, neurotransmitters, and evolutionary pressures, you can begin to unravel the complexities of dissociation, fostering greater compassion for yourself and others, and paving the way for recovery and integration. Your journey towards understanding this biological marvel is a journey towards deeper self-knowledge and resilience.

THE DPDR EXIT PLAN: WARNING: Your Brain Is Stuck In “Safety Mode”

FAQs

What are dissociative defense responses?

Dissociative defense responses are psychological mechanisms that involve a disconnection or disruption in consciousness, memory, identity, or perception. They often occur as a way to cope with traumatic or stressful experiences by temporarily distancing oneself from reality.

Which brain regions are involved in dissociative defense responses?

Key brain regions involved include the prefrontal cortex, which regulates executive functions and emotional control; the amygdala, which processes emotions such as fear; the hippocampus, important for memory formation; and the anterior cingulate cortex, which plays a role in attention and emotional regulation. Altered activity in these areas is associated with dissociative states.

How does neurobiology explain the occurrence of dissociation during trauma?

Neurobiological models suggest that during extreme stress or trauma, the brain may activate dissociative responses to protect the individual from overwhelming emotional pain. This involves changes in neural circuits related to threat detection, emotional regulation, and consciousness, leading to symptoms such as depersonalization, derealization, or amnesia.

Are there neurotransmitters linked to dissociative defense mechanisms?

Yes, neurotransmitters such as glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin, and norepinephrine are implicated in dissociative processes. For example, dysregulation of glutamate and GABA systems can affect neural excitability and inhibition, contributing to altered states of consciousness seen in dissociation.

Can understanding the neurobiology of dissociation improve treatment approaches?

Absolutely. Insights into the neural mechanisms underlying dissociative defense responses can guide the development of targeted therapies, including pharmacological interventions and psychotherapeutic techniques, to better manage dissociative symptoms and improve outcomes for individuals with trauma-related disorders.