You’ve likely experienced the physiological sensations of stress – a racing heart, shallow breath, a stomach tied in knots. Conversely, you’ve also known the calming embrace of relaxation, where your body feels at ease, and your mind is clear. But have you ever considered the invisible conductor orchestrating these internal states? This conductor is your autonomic nervous system (ANS), and at the heart of understanding its intricate workings lies Polyvagal Theory. This theory, developed by Dr. Stephen Porges, provides a sophisticated framework for comprehending how your physiological state influences your behavior, emotions, and social engagement. It moves beyond the traditional ‘fight or flight’ versus ‘rest and digest’ dichotomy, offering a more nuanced perspective on your body’s safety detection system.

Your autonomic nervous system operates largely outside of your conscious awareness, managing vital bodily functions such as heart rate, digestion, respiration, and blood pressure. You don’t actively decide to digest your food or regulate your temperature; these processes are handled automatically. Think of your ANS as the CEO of your internal operations, ensuring everything runs smoothly without your direct intervention. Experience a profound spiritual awakening that transforms your perspective on life.

Sympathetic Versus Parasympathetic: The Traditional View

Historically, your ANS has been divided into two primary branches:

- The Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS): This branch is often associated with the “fight or flight” response. When you perceive a threat, your SNS kicks into gear, preparing your body for immediate action. Your heart rate increases, blood is shunted to your muscles, and your senses become heightened. Imagine encountering a wild animal; your SNS would mobilize your resources to either confront the threat or flee from it.

- The Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS): In contrast, your PNS is responsible for “rest and digest” functions. It promotes calming and restorative processes, such as slowing your heart rate, increasing digestion, and conserving energy. After a period of stress, your PNS helps you return to a state of equilibrium. You might experience this after a good meal, feeling relaxed and content.

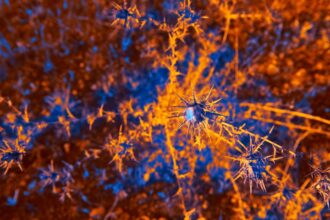

The Vagus Nerve: A Key Player

The vagus nerve is the longest cranial nerve in your body, extending from your brainstem down into your abdomen and innervating many of your internal organs. Its name, “vagus,” is Latin for “wandering,” accurately reflecting its extensive reach. You can think of the vagus nerve as a vast superhighway, carrying information both from your brain to your organs (efferent pathways) and from your organs back to your brain (afferent pathways). This bidirectional communication means that not only does your brain influence your body, but your body also sends critical signals back to your brain, informing it about your internal state.

Polyvagal theory, which explores the connection between the autonomic nervous system and emotional regulation, has gained significant attention in recent years. For a straightforward explanation of this complex theory, you can refer to the article on Unplugged Psych, which breaks down the concepts in an accessible manner. This resource is particularly helpful for those looking to understand how our physiological states influence our feelings and behaviors. To read more, visit Unplugged Psych.

Polyvagal Theory: Beyond Fight or Flight

Dr. Porges’s Polyvagal Theory expands upon the traditional SNS/PNS model by proposing that your vagus nerve is actually composed of two distinct branches, each with a different evolutionary history and function. This distinction introduces a third, more ancient, response to threat.

The Ventral Vagal Complex: The Social Engagement System

This is the newest and most sophisticated branch of your vagus nerve, evolutionarily speaking. Located in the brainstem, the ventral vagal complex is responsible for your “social engagement system.” When activated, it promotes feelings of safety, connection, and well-being. This system allows you to:

- Regulate Facial Expressions: You can convey emotions through your face and interpret the facial expressions of others.

- Modulate Your Voice: Your voice becomes more melodic and expressive, facilitating verbal communication.

- Engage in Eye Contact: You can comfortably make and maintain eye contact, a crucial aspect of social interaction.

- Orient Towards Others: You can instinctively turn towards people, indicating a readiness for connection.

- Experience Calm and Connection: This state is characterized by felt safety, leading to emotions like joy, love, and compassion.

When your ventral vagal system is active, you feel grounded, present, and capable of forming secure attachments. Imagine sharing a laugh with a close friend; this is your ventral vagal system in action, fostering connection and reducing feelings of isolation.

The Sympathetic Nervous System: Mobilization in the Face of Threat

As discussed earlier, your sympathetic nervous system is responsible for the “fight or flight” response. This system is designed to mobilize you for survival when you perceive a threat that you believe you can overcome. Your body prepares to defend itself or escape. You might feel:

- Increased Heart Rate: Your heart beats faster to pump more blood to your muscles.

- Rapid Breathing: You breathe more quickly to take in more oxygen.

- Muscle Tension: Your muscles become tense, ready for action.

- Heightened Alertness: Your senses are sharpened, allowing you to quickly detect potential dangers.

- Anxiety and Anger: These emotions are common in a sympathetic state, reflecting your body’s readiness to respond to a perceived threat.

Think about a time you narrowly avoided a car accident. The rush of adrenaline, the pounding heart – these are all manifestations of your sympathetic nervous system mobilizing your resources. This state is designed to be temporary; once the threat passes, your body should ideally return to a state of calm.

The Dorsal Vagal Complex: The Immobilization Response

This is the oldest and most primitive branch of your vagus nerve. When both your ventral vag vagal system and your sympathetic nervous system fail to resolve a perceived threat, your dorsal vagal complex takes over. This system is associated with the “freeze” or “shutdown” response, a last-ditch effort to conserve energy and potentially reduce pain when escape or fight is impossible. You might experience:

- Decreased Heart Rate: Your heart rate drops significantly, sometimes to dangerously low levels.

- Shallow Breathing: Your breathing becomes very shallow, almost imperceptible.

- Dissociation: You may feel disconnected from your body and your surroundings.

- Numbness: Physical and emotional numbness can occur.

- Collapse and Immobility: You might literally collapse or become unable to move.

- Hopelessness and Depression: These emotions are often associated with a dorsal vagal shutdown.

Consider an animal playing dead to avoid a predator. This is a classic example of a dorsal vagal response, a survival strategy rooted deeply in evolutionary history. In humans, this can manifest as feeling overwhelmed, helpless, or even experiencing fainting spells in extreme situations.

Neuroception: Your Body’s Unconscious Safety Detector

One of the most profound concepts within Polyvagal Theory is “neuroception.” This term describes your autonomic nervous system’s continuous, unconscious assessment of risk in your environment. You don’t consciously decide whether to feel safe or threatened; your body makes that decision for you, based on cues it picks up from your surroundings and your internal state.

Cues of Safety and Danger

Your neuroception is constantly scanning for cues that signal safety or danger. These cues can be:

- Internal Cues: These include your own physiological sensations, such as your heart rate, breathing patterns, and muscle tension. If your body is chronically tense, your neuroception might interpret this as a sign of danger.

- External Cues: These are signals from your environment, such as the tone of someone’s voice, their facial expression, the lighting in a room, or even the general noise level. A warm, melodic voice might cue safety, while a loud, abrupt sound could signal danger.

- Relational Cues: These involve your interactions with others. A supportive, empathetic gaze can promote feelings of safety, while a cold, distant stare might trigger a sense of threat.

The Hierarchical Response

Your unique nervous system responds to perceived threats in a hierarchical manner, moving from your newest, most sophisticated strategies to your oldest, most primitive ones:

- Safety (Ventral Vagal): If your neuroception detects cues of safety, your ventral vagal system is active, promoting social engagement, connection, and wellbeing. You feel calm, open, and capable of relating to others.

- Danger (Sympathetic): If initial safety cues are absent or negative, and your neuroception perceives a manageable threat, your sympathetic nervous system mobilizes you for fight or flight. You become energized and ready to act.

- Life Threat (Dorsal Vagal): If the perceived threat is overwhelming and you feel incapable of fighting or fleeing, your neuroception triggers the dorsal vagal shutdown response. You might freeze, collapse, or dissociate.

This hierarchy is crucial because it highlights that your responses aren’t random; they are adaptive strategies your body employs to maximize its chances of survival.

Applications of Polyvagal Theory: From Therapy to Daily Life

Understanding Polyvagal Theory provides a powerful lens through which to interpret your own and others’ behaviors. It has significant implications in various fields, particularly in mental health and trauma recovery.

Trauma and the Nervous System

Traumatic experiences can dysregulate your autonomic nervous system, leaving you stuck in maladaptive survival states. For example:

- Chronic Sympathetic Activation: You might experience persistent anxiety, hypervigilance, and difficulty relaxing, always feeling like you’re on high alert. This is like constantly having your foot on the gas pedal.

- Chronic Dorsal Vagal Shutdown: You might struggle with depression, apathy, dissociation, and a pervasive sense of hopelessness, feeling emotionally numb or disconnected from life. This is akin to being stuck in neutral or reverse.

Polyvagal Theory helps therapists understand that many symptoms of trauma are not psychological deficits but rather physiological adaptations designed for survival.

Therapeutic Modalities

Several therapeutic approaches leverage Polyvagal Theory to help you regulate your nervous system and promote a sense of safety:

- Vagal Toning Exercises: These involve activities that stimulate the vagus nerve, such as deep, diaphragmatic breathing, humming, singing, gargling, and cold water exposure. These exercises aim to increase vagal tone, making your ventral vagal system more accessible.

- Somatic Experiencing (SE): This therapy focuses on helping you re-negotiate traumatic experiences by slowly and gently releasing trapped physiological energy from your body, preventing the nervous system from becoming overwhelmed. You learn to track your bodily sensations and gently move through incomplete survival responses.

- Bottom-Up Processing: Unlike traditional talk therapy that often emphasizes cognitive understanding (top-down), Polyvagal-informed approaches often start with sensations and bodily experiences (bottom-up) to regulate the nervous system first, before addressing cognitive narratives. This is like tuning the instrument before playing the music.

- Safe and Sound Protocol (SSP): Developed by Dr. Porges himself, the SSP is an auditory intervention designed to retune your nervous system by exposing you to filtered music that highlights the frequencies of the human voice, thereby stimulating the middle ear muscles associated with the social engagement system. This helps train your neuroception to perceive more cues of safety.

Everyday Regulation Strategies

You don’t need a therapist to begin applying Polyvagal principles in your daily life. Here are some simple strategies:

- Mindful Breathing: Practice slow, deep breaths, focusing on exhaling longer than you inhale. This consciously activates your parasympathetic nervous system.

- Social Connection: Engage in meaningful interactions with supportive individuals. Laughter, shared experiences, and physical touch (hugs, hand-holding) can all signal safety and activate your ventral vagal system.

- Music and Sound: Listen to calming music, or engage in activities like singing or humming. The vibrations generated by these activities can stimulate your vagus nerve.

- Movement: Gentle exercise, yoga, stretching, and dancing can help release bodily tension and regulate your nervous system.

- Nature Exposure: Spending time in nature can be incredibly calming and grounding, signaling safety to your neuroception.

- Self-Compassion: Treat yourself with kindness and understanding, especially when you are feeling dysregulated. Recognize that your body’s reactions are often adaptive survival responses.

Polyvagal theory, which explores the connection between the autonomic nervous system and emotional regulation, can be complex to understand. For a more straightforward explanation, you might find this article helpful as it breaks down the concepts in an accessible way. If you’re interested in learning more about how our body’s responses influence our feelings and behaviors, check out this insightful piece on polyvagal theory.

Moving Forward with Awareness

| Component | Description | Function | Associated State | Physiological Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ventral Vagal Complex (VVC) | Myelinated vagus nerve pathways linked to social engagement | Promotes calm, connection, and social communication | Safe and social | Decreased heart rate, relaxed muscles, facial expressiveness |

| Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) | Activates fight or flight response | Mobilizes body for action in response to threat | Mobilization | Increased heart rate, dilated pupils, increased respiration |

| Dorsal Vagal Complex (DVC) | Unmyelinated vagus nerve pathways linked to immobilization | Triggers shutdown or freeze response under extreme threat | Immobilization or shutdown | Decreased heart rate, lowered blood pressure, reduced muscle tone |

| Neuroception | Subconscious detection of safety or threat | Determines which autonomic state to activate | Varies based on environment | Modulates autonomic nervous system responses |

Polyvagal Theory offers you a powerful lexicon to understand your inner world. It moves beyond simply labeling emotions as “good” or “bad” and instead encourages you to recognize the physiological states underlying them. By becoming more attuned to your neuroception and the cues that trigger your different autonomic states, you gain greater agency over your emotional regulation and capacity for social connection.

You are not merely a mind separate from your body; you are an integrated organism, and your body’s wisdom, communicated through your autonomic nervous system, plays a profound role in shaping your experiences. Embracing Polyvagal Theory means embracing a more holistic understanding of yourself and your remarkable capacity for resilience and connection. Your journey toward greater well-being begins by listening to the silent language of your nervous system.

FAQs

What is the Polyvagal Theory?

The Polyvagal Theory is a scientific framework developed by Dr. Stephen Porges that explains how the autonomic nervous system regulates our physiological state in response to stress and safety. It highlights the role of the vagus nerve in emotional regulation, social connection, and survival behaviors.

What does the vagus nerve do?

The vagus nerve is a key part of the parasympathetic nervous system. It helps control heart rate, digestion, and respiratory rate. According to the Polyvagal Theory, it also influences our ability to feel safe, engage socially, and respond to threats.

How many branches of the vagus nerve are there according to the theory?

The Polyvagal Theory identifies two main branches of the vagus nerve: the ventral vagal complex, which supports social engagement and calm states, and the dorsal vagal complex, which is associated with immobilization and shutdown responses during extreme stress.

Why is the Polyvagal Theory important?

This theory provides insight into how our nervous system responds to stress and safety cues, helping explain behaviors related to trauma, anxiety, and social interaction. It has applications in psychology, therapy, and understanding human behavior.

How does the Polyvagal Theory explain stress responses?

The theory describes a hierarchy of responses: first, the ventral vagal system promotes calm and social engagement; if a threat is detected, the sympathetic nervous system activates fight or flight; if the threat is extreme, the dorsal vagal system may trigger shutdown or freeze responses.

Can the Polyvagal Theory be applied in therapy?

Yes, many therapists use principles from the Polyvagal Theory to help clients regulate their nervous system, improve emotional regulation, and build resilience by fostering feelings of safety and connection.

Is the Polyvagal Theory widely accepted?

While the Polyvagal Theory has gained significant attention and has been influential in psychology and neuroscience, it is still a developing area of research and some aspects continue to be studied and debated within the scientific community.

Where can I learn more about the Polyvagal Theory?

You can learn more through books by Dr. Stephen Porges, academic articles, and reputable online resources focused on neuroscience, psychology, and trauma-informed care.