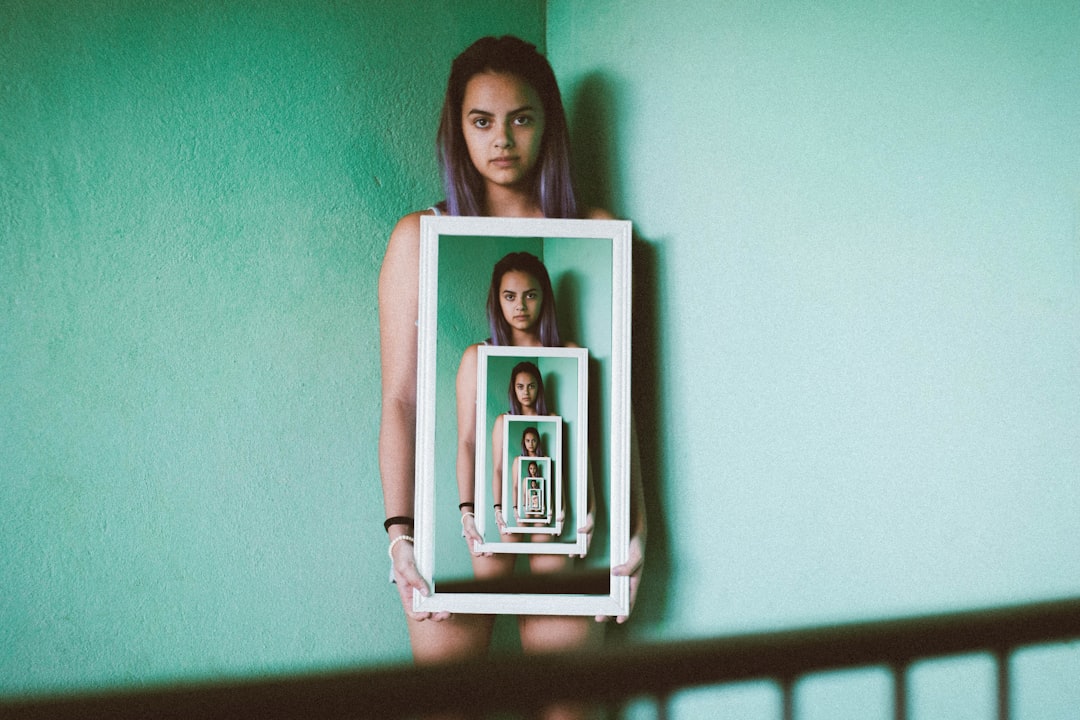

When you encounter the terms “detachment” and “dissociation,” it’s easy to conflate them. Both describe a sense of mental separation from your thoughts, feelings, or surroundings. However, they represent distinct psychological phenomena with different causes, characteristics, and implications for your well-being. To truly understand these states, imagine them as two different kinds of distance you might experience from a situation. Detachment is like stepping back to gain perspective, a deliberate act of observation. Dissociation, on the other hand, is like a sudden, involuntary fog descending, altering your connection to reality itself.

The Nature of Detachment: A Conscious Stepping Back

Detachment, at its core, is a conscious and often intentional psychological process. You choose to create a mental distance between yourself and a particular thought, feeling, person, or situation. This doesn’t mean you cease to care or feel; rather, you gain the ability to observe without being overwhelmed or unduly influenced. Think of it as an emotional buffer you employ.

Intentionality and Control

A key differentiator for detachment is that you largely maintain control over the experience. You can choose when to detach and when to re-engage. For instance, you might intentionally detach from a stressful work situation during your evening hours to prevent burnout, or you might emotionally detach from a difficult conversation with a family member to avoid an escalating argument. This intentionality gives you agency over your emotional regulation.

Adaptive Functions of Detachment

Detachment serves several important adaptive functions in your life. It can be a vital tool for mental and emotional resilience.

Stress Management

When you face high-stress environments, such as a demanding job or a crisis, detaching can help you maintain a clear head. You observe the events unfolding without being engulfed by the emotional intensity, allowing for more rational decision-making. You’re like a commander observing a battle from a tactical distance, rather than being in the thick of the fray.

Emotional Regulation

Learning to detach from intense emotions, such as anger or anxiety, allows you to process them more effectively. Instead of reacting impulsively, you can take a step back and examine the emotion, understand its triggers, and choose a more constructive response. This isn’t about suppressing feelings, but about observing them without being hijacked by them. You acknowledge the emotion’s presence without letting it dictate your actions.

Setting Boundaries

Detachment is fundamental to establishing healthy personal boundaries. When you detach from another person’s emotional turmoil, you prevent their distress from becoming your own. This protects your emotional energy and allows you to offer support without sacrificing your well-being. It is the ability to say, “I see your pain, but it is not mine to carry.”

Objectivity and Problem Solving

In situations requiring an objective perspective, detachment is invaluable. Scientists detach from their personal biases to interpret data. Judges detach from personal opinions to apply the law fairly. You, too, can use detachment to critically analyze problems, separate facts from emotions, and develop more effective solutions.

The Nature of Dissociation: An Involuntary Disconnection

Dissociation, in contrast to detachment, is an involuntary mental process where there is a disruption in the normal integrated functions of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, and behavior. It is not a choice you make; rather, it is a defensive mechanism, often triggered by stress or trauma, that your mind employs without your conscious consent. Imagine your mind putting up a sudden, impenetrable壁 (wall) between you and your experience, rather than just a transparent pane of glass.

Involuntariness and Loss of Control

Unlike detachment, you typically have little to no conscious control over dissociative experiences. They can arise suddenly and unexpectedly, leaving you feeling disoriented and disconnected. You may struggle to “snap out of it” even when you recognize what is happening. This lack of control is a hallmark of dissociation and can be deeply distressing.

Spectrum of Dissociative Experiences

Dissociation exists on a spectrum, ranging from mild, transient experiences to severe, chronic conditions.

Everyday Dissociation

You might experience mild forms of dissociation in daily life without even realizing it. These are often fleeting instances and less impactful.

“Highway Hypnosis”

Driving a familiar route and suddenly realizing you have no memory of the last few miles is a common example. Your mind was “elsewhere” while your body performed the automatic task. You were present in body, but not fully in mind.

Becoming Absorbed

When you’re deeply engrossed in a book, movie, or creative task, you might lose track of time or your surroundings. While a form of mental absorption, if it becomes pervasive or involuntary, it can lean towards dissociative tendencies.

Pathological Dissociation

At the more severe end of the spectrum, dissociation manifests as significant disruptions to your sense of self, memory, and reality. These are often indicative of dissociative disorders.

Depersonalization

This involves feeling detached from your own body, thoughts, feelings, or actions. You might feel as if you are observing yourself from the outside, like an actor in a play, or that your body isn’t truly yours. “I feel like I’m not real,” or “I feel like a robot,” are common descriptions.

Derealization

This is a feeling of unreality or detachment from your surroundings. The world might appear distorted, dreamlike, foggy, or unfamiliar, even places you know well. “The world doesn’t feel real,” or “People look like actors,” are typical expressions.

Amnesia

Dissociative amnesia involves an inability to recall important personal information, usually of a traumatic or stressful nature, that is too extensive to be explained by ordinary forgetfulness. This isn’t about forgetting where you put your keys; it’s about significant gaps in your personal history.

Identity Confusion/Alteration

In severe cases, such as Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), you might experience significant alterations in your sense of self, with distinct identities or “alters” emerging. This is the most profound form of dissociative experience, where the very core of who you are becomes fragmented.

Distinguishing the Two: Key Differences and Overlaps

While distinct, it’s important to recognize that in some contexts, the line between detachment and mild dissociation can feel blurry, particularly during periods of intense stress. However, fundamental differences remain.

Underlying Mechanisms

Detachment is primarily a cognitive process, a conscious decision to alter your focus and emotional engagement. It’s like manually adjusting your mental zoom lens. Dissociation, on the other hand, is considered an automatic, unconscious defense mechanism, often rooted in attempts to cope with overwhelming experiences, particularly trauma. It’s like your mental circuit breaker automatically tripping to prevent overload.

Relationship to Trauma

While you might use healthy detachment to cope with everyday stressors, severe or chronic dissociation is strongly linked to trauma and adverse childhood experiences. It’s your mind’s way of creating a psychological escape route when real escape is impossible or perceived to be impossible.

Impact on Functioning

Healthy detachment generally enhances your functioning, allowing you to manage stress and make better decisions. Pathological dissociation, conversely, tends to impair functioning, leading to memory problems, identity confusion, emotional dysregulation, and difficulties in relationships and daily life. You might struggle to maintain consistent social interactions or hold down a job because of these disruptions.

Awareness and Insight

When you are healthily detached, you are typically aware of this state and maintain a strong sense of self and reality. You know you are choosing to step back. During a dissociative episode, especially a severe one, your awareness of your surroundings or even your own identity can be significantly impaired. You might not fully realize what is happening, or you might perceive it as a strange, unexplainable shift in reality.

When to Seek Professional Help

Understanding the difference between detachment and dissociation is critical for knowing when to seek support.

When Detachment Becomes Problematic

Even healthy detachment can become maladaptive if it is used excessively or inappropriately.

Chronic Emotional Numbness

If you find yourself constantly detached from your emotions, even in situations where emotional engagement would be appropriate or beneficial, it might indicate a more profound issue. A persistent inability to feel joy, sorrow, or connection can be a sign. You might feel a pervasive emptiness, a “flatness” that permeates all aspects of your life.

Interpersonal Difficulties

If your use of detachment leads to chronic difficulty forming or maintaining meaningful relationships, or if others frequently accuse you of being cold, uncaring, or distant, it’s worth exploring. While boundaries are healthy, emotional walls that prevent genuine connection are not.

Avoidance of Important Issues

If you consistently use detachment to avoid confronting difficult but necessary truths or responsibilities in your life, it can hinder your personal growth and problem-solving abilities. It becomes a shield against facing reality, rather than a tool for managing it.

When Dissociation Necessitates Intervention

If you experience any form of pathological dissociation, especially if it is frequent, prolonged, or impairs your daily functioning, professional help is highly recommended.

Recurring Episodes of Unreality

If you frequently experience feelings of depersonalization or derealization, where you or your surroundings feel consistently unreal or dreamlike. This isn’t just a fleeting odd sensation, but a pervasive alteration of your reality.

Gaps in Memory or Time

If you discover significant gaps in your memory that cannot be explained by normal forgetfulness, or if you lose track of hours or days, this is a strong indicator for concern. You might find objects you don’t remember acquiring, or be told about conversations you have no recollection of.

Feeling Like You Have “Lost Time”

Similar to memory gaps, if you frequently experience periods where you feel like you’ve “blacked out” or lost time, even without substance use, it points towards a dissociative process.

Identity Confusion or Multiple Selves

If you feel confused about who you are, experience shifts in your sense of identity, or feel as though there are “other people” inside you, these are critical signs requiring immediate professional attention. This involves fundamental disruptions to your core sense of self.

Significant Impact on Daily Life

Any dissociative experience that interferes with your ability to work, study, maintain relationships, or care for yourself necessitates professional support. It’s not just an odd feeling, but something actively hindering your ability to navigate the world.

Cultivating Healthy Detachment and Addressing Dissociation

Understanding these two states empowers you to cultivate healthier mental habits and seek appropriate care.

Strategies for Healthy Detachment

If you aim to develop your capacity for healthy detachment, consider these approaches.

Mindfulness and Meditation

Practices that encourage you to observe your thoughts and feelings without judgment are excellent for developing a detached perspective. When you engage in mindfulness, you are like an impartial observer of your internal landscape, rather than being swept away by the currents.

Cognitive Reframing

Learning to consciously reframe negative thoughts or challenging situations from a different perspective can help you create mental distance and reduce emotional reactivity. You actively choose a different lens through which to view your experiences.

Setting Boundaries

Actively practicing saying “no,” limiting exposure to draining individuals or situations, and defining what you are and are not responsible for are essential components of healthy detachment. You are literally drawing lines to protect your mental space.

Addressing Dissociation

If you suspect you are experiencing pathological dissociation, the path forward involves professional intervention.

Therapy

Trauma-informed therapy, such as Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), can be highly effective. These therapies help you process traumatic memories, develop coping skills, and integrate fragmented aspects of your self. A qualified therapist can guide you through the process of reconnecting with your experiences in a safe and structured manner.

Support Systems

Building a strong support network of trusted friends, family, or support groups can provide validation and reduce feelings of isolation. Sharing your experiences in a safe environment can be incredibly healing.

Self-Care and Grounding Techniques

Learning grounding techniques (e.g., focusing on sensory input, physical exercise, deep breathing) can help you orient yourself to the present moment during dissociative episodes. These techniques help anchor you when you feel adrift. Prioritizing sleep, nutrition, and stress reduction also contributes to overall mental stability.

In conclusion, while both detachment and dissociation involve a form of mental separation, their origins, nature, and impact are fundamentally different. Detachment is a conscious, adaptive tool you wield for emotional regulation and clarity. Dissociation is an unconscious, often trauma-driven defense mechanism that disrupts your connection to self and reality. By understanding these distinctions, you can better navigate your internal experiences, foster emotional resilience, and know when to reach out for the specialized support that can guide you back to a more integrated and connected sense of self.

WARNING: Your “Peace” Is Actually A Trauma Response

FAQs

What is the primary difference between detachment and dissociation?

Detachment generally refers to a conscious process of emotionally distancing oneself from a situation or person, often to maintain objectivity or protect oneself. Dissociation, on the other hand, is an involuntary psychological response where a person disconnects from their thoughts, feelings, memories, or sense of identity, often as a coping mechanism during trauma or stress.

Can detachment be a healthy coping mechanism?

Yes, detachment can be a healthy way to manage emotions by creating boundaries and maintaining perspective. It allows individuals to avoid becoming overwhelmed by intense feelings and to respond more rationally to challenging situations.

Is dissociation always a sign of a mental health disorder?

Not necessarily. While dissociation can be a symptom of mental health disorders such as dissociative identity disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), mild dissociative experiences can occur in the general population during stress or fatigue. However, frequent or severe dissociation may require professional evaluation.

How do detachment and dissociation affect emotional awareness?

Detachment involves a conscious choice to regulate emotional involvement, often preserving emotional awareness. Dissociation typically involves a disruption or loss of emotional awareness, where the person may feel numb, disconnected, or unaware of their feelings.

Can both detachment and dissociation be reversed or managed?

Detachment is usually reversible and can be adjusted based on the individual’s needs and circumstances. Dissociation can also be managed or treated, especially with therapeutic interventions such as psychotherapy, but may require professional support depending on its severity and underlying causes.