You are hardwired for connection. From the moment you draw your first breath, your very survival hinges on the proximity and care of another. This primal need, etched into your biological blueprint, evolves into a complex tapestry of relationships that weave through the fabric of your existence. This is the addictive nature of human attachment, a force as potent as any chemical dependency, shaping your thoughts, driving your behaviors, and ultimately defining your lived experience.

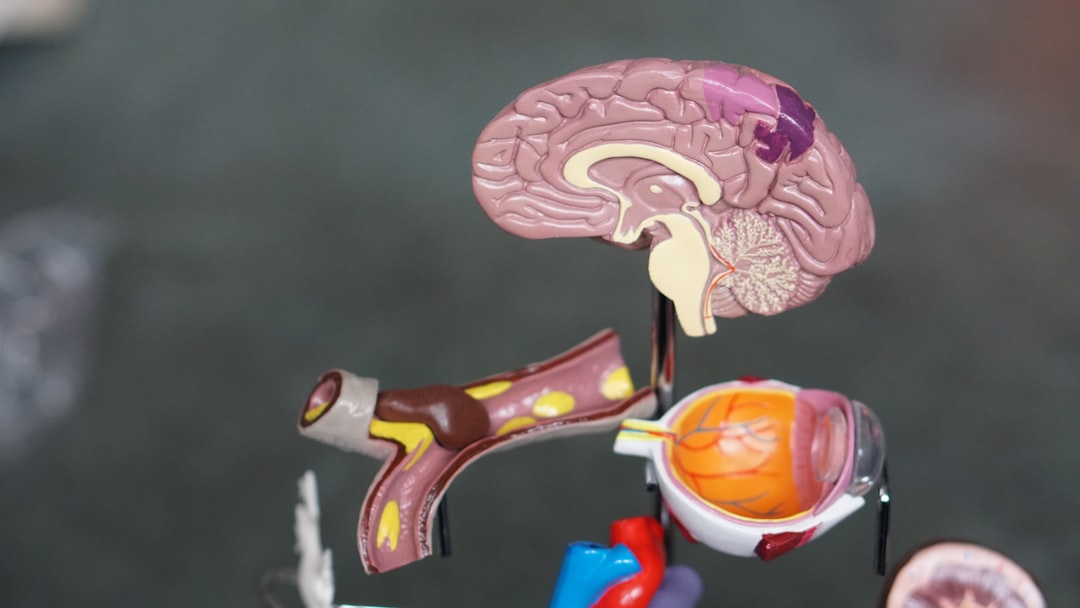

Your brain is a finely tuned orchestra, and attachment plays a crucial role in its composition. When you form bonds, a cascade of neurochemicals is released, creating a euphoric sensation that reinforces the desire for further connection.

Oxytocin: The “Love Hormone”

You’ve likely heard of oxytocin, often dubbed the “love hormone.” This peptide neurotransmitter plays a pivotal role in social bonding, trust, and empathy. It is released during physical touch, such as hugging and kissing, and is instrumental in the maternal-infant bond, facilitating caregiving behaviors. When you experience positive social interactions, your oxytocin levels surge, creating a feeling of warmth and security. This physiological response is a fundamental pillar of attachment, making you crave its comforting embrace. Think of oxytocin as the gentle conductor, guiding the orchestra of your social brain towards harmony and connection.

Dopamine: The Reward System

Beyond oxytocin, dopamine also plays a critical role. This neurotransmitter is famously associated with pleasure and reward. When you engage in activities that fulfill your attachment needs, such as receiving affection or experiencing shared joy, your dopamine levels increase. This creates a positive feedback loop, reinforcing the behaviors that lead to these rewarding experiences. It’s the tantalizing sparkle of a potential reward, fueling your drive to seek out and maintain those connections. Dopamine acts as the motivating force, pushing you towards the sweet notes of reciprocated affection.

Serotonin: Modulating Mood and Well-being

Serotonin, another crucial neurotransmitter, influences your mood, sleep, and appetite. When your attachment needs are met, serotonin levels tend to be stable, contributing to a sense of contentment and well-being. Conversely, disruptions in attachment can lead to imbalances in serotonin, underscoring the profound impact of social connection on your mental state. Serotonin, in this context, is the steady rhythm section, maintaining a balanced and harmonious flow.

The intricate relationship between addiction mechanisms and human attachment is explored in depth in a related article on the Unplugged Psych website. This piece delves into how attachment styles can influence susceptibility to various forms of addiction, highlighting the psychological underpinnings that connect emotional bonds to addictive behaviors. For further insights, you can read the article here: Unplugged Psych.

The Evolutionary Imperative: Survival Through Proximity

Attachment isn’t merely a pleasant byproduct of social living; it is a deeply ingrained evolutionary adaptation that has propelled the survival of your species for millennia. The ability to form strong bonds significantly increased the chances of survival for both individuals and offspring.

The Vulnerability of the Neonate

Consider the immense vulnerability of a newborn human. Unlike many other species, human infants are born remarkably undeveloped, requiring prolonged periods of intensive care. Your capacity to form an intense bond with your caregivers ensured that you received the nourishment, protection, and stimulation necessary to grow and thrive. This biological imperative to stay close to the caregiver, the primary source of safety, is a fundamental aspect of your innate attachment drive. Imagine yourself as a tiny sapling; the sturdy trunk of parental care is what allows you to reach towards the sun.

The Benefits of Group Cohesion

Beyond the infant-parent dyad, attachment extends to wider social groups. Early humans who formed cooperative bonds within tribes benefited from increased safety, shared resources, and more effective hunting and defense strategies. This group cohesion, facilitated by mutual attachment and trust, provided a significant evolutionary advantage. The strength of a pack lies not in the individual wolf, but in the intertwined threads of their loyalty and shared purpose.

The Drive for Social Acceptance

The fear of ostracization, or social exclusion, is a potent motivator deeply rooted in this evolutionary past. Being cast out from the group meant a drastic reduction in survival prospects. This explains why you often feel a strong internal pressure to conform, to be accepted, and to avoid situations that might lead to rejection. This instinctual aversion to solitude is a powerful echo of your ancestors’ need for communal security.

The Formation of Attachment Styles: Early Blueprints

The patterns of connection you establish in early childhood, particularly with your primary caregivers, lay the groundwork for your future relationships. These patterns, known as attachment styles, are like invisible blueprints that guide your approach to intimacy and connection throughout life.

Secure Attachment: The Foundation of Trust

If your early caregivers were responsive, consistent, and attuned to your needs, you likely developed a secure attachment style. For you, this means a fundamental belief that others are reliable and trustworthy. You are comfortable with both intimacy and independence, able to form close bonds without excessive anxiety or fear of abandonment. Your internal working model of relationships is one of safety and predictability. You navigate the landscape of connection with a well-worn compass, confident in your direction.

Insecure-Avoidant Attachment: The Shield of Independence

If your early caregivers were emotionally distant or unresponsive, you might have developed an insecure-avoidant attachment style. You may have learned to suppress your needs for closeness to avoid rejection or disappointment. This can manifest as a preference for independence, a reluctance to rely on others, and a discomfort with emotional intimacy. You might appear self-sufficient, but beneath the surface, there can be a hidden fear of vulnerability. Think of this as building a high wall around yourself, a fortress designed to keep perceived threats at bay.

Insecure-Ambivalent/Anxious Attachment: The Constant Need for Reassurance

Conversely, if your caregivers were inconsistent in their responsiveness, sometimes attentive and other times neglectful, you may have developed an insecure-ambivalent or anxious attachment style. This can lead to a strong desire for closeness, coupled with a pervasive fear of abandonment. You might be prone to jealousy, constantly seeking reassurance from your partners. Your internal experience can be one of heightened emotional reactivity and a persistent, gnawing anxiety about the stability of your relationships. You might be like a tightly wound spring, perpetually on the verge of release, seeking to be held lest you unravel.

Disorganized Attachment: The Unpredictable Landscape

A more complex pattern, disorganized attachment, can emerge when caregivers are perceived as frightening or unpredictable, sometimes being a source of comfort and other times a source of fear. This can lead to contradictory behaviors in relationships, a difficulty in regulating emotions, and a profound sense of unease and confusion regarding intimacy. The internal landscape here is one of shifting sands, where stability is elusive.

The Pull of the Familiar: Why We Replay Patterns

Even when you recognize unhealthy patterns in your relationships, the gravitational pull of the familiar can be incredibly strong. This tendency to gravitate towards people and situations that mirror your early attachment experiences, even if they are detrimental, is a testament to the power of ingrained psychological imprints.

The Comfort of the Known

Your brain is wired to seek predictability. Familiar attachment patterns, even those associated with distress, can feel more comfortable than the uncertainty of new and different relational dynamics. It’s like returning to a well-trodden path, even if it’s a muddy and winding one, because you know what to expect. The devil you know, as the saying goes, can feel safer than the one you don’t.

The Unconscious Drive for Resolution

There can also be an unconscious drive to revisit and “resolve” unresolved issues from your past. By recreating familiar relational scenarios, you may be unknowingly seeking an opportunity to achieve a different outcome, to finally gain the validation or security that was missing in your childhood. This is a subtle and often subconscious attempt to rewrite your personal narrative. It’s like a broken record, looping the same melody, hoping for a different ending each time.

The Role of Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases also play a role. You might interpret ambiguous behaviors of a new partner through the lens of your established attachment patterns, inadvertently seeking out evidence that confirms your existing beliefs about relationships. Confirmation bias, in this instance, acts as a filter, highlighting what aligns with your pre-existing internal models.

Research into the addiction mechanism in human attachment reveals fascinating insights into how our relationships can mirror the patterns of substance dependence. A related article that delves deeper into this topic can be found at Unplugged Psych, where the complexities of emotional bonds and their impact on mental health are explored. Understanding these dynamics can help individuals navigate their connections more effectively and foster healthier relationships.

The Addiction Cycle: Seeking and Withdrawal

| Metric | Description | Typical Values/Observations | Relevance to Addiction Mechanism in Human Attachment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine Release | Amount of dopamine released in the brain’s reward pathways during attachment interactions | Increased by 50-100% during positive social bonding | Drives reward-seeking behavior similar to substance addiction |

| Oxytocin Levels | Concentration of oxytocin hormone during attachment and bonding | Elevated by 30-70% during close social contact | Enhances feelings of trust and attachment, reinforcing bonding |

| Withdrawal Symptoms | Emotional and physiological symptoms experienced during separation | Increased anxiety, craving, and stress hormone levels | Similar to withdrawal in substance addiction, indicating dependency |

| Attachment Anxiety Score | Psychological measure of anxiety related to attachment insecurity | Scale from 1 (low) to 7 (high); average around 3-4 in general population | Higher scores correlate with addictive attachment behaviors |

| Endorphin Activity | Level of endogenous opioids released during social bonding | Increased by 20-50% during positive social interactions | Contributes to pleasure and pain relief, reinforcing attachment |

| Stress Hormone (Cortisol) Levels | Concentration of cortisol during attachment disruption or loss | Elevated by 40-80% during separation or rejection | Triggers craving and seeking behaviors to restore attachment |

The addictive nature of attachment is clearly demonstrated in the cyclical pattern of seeking connection and experiencing withdrawal when it is disrupted. This mirrors the neurochemical and behavioral pathways seen in substance addiction.

The Rush of Connection: The Reinforcing Stimulus

When you are in a relationship that fulfills your attachment needs, the experience can be highly reinforcing. The influx of positive neurochemicals, the sense of belonging, and the affirmation of your worth create a powerful “high.” This experience acts as a potent stimulus, driving your desire to maintain and deepen the connection. Think of it as the initial rush of a drug, promising euphoria and satisfaction.

The Agony of Separation: Withdrawal Symptoms

When that connection is threatened or lost, you can experience withdrawal-like symptoms. These can include feelings of intense longing, anxiety, sadness, and even physical discomfort. The absence of the familiar relational stimulus can trigger a cascade of negative emotions and a desperate urge to re-establish the bond. This is the “crash” that follows the high, leaving you feeling depleted and distressed. The void left by the absence of attachment can feel like an emptiness that screams to be filled.

The Relapse: Returning to the Familiar

Just as an addict may relapse to a familiar substance or behavior, you may find yourself drawn back to former partners or types of relationships that, despite their flaws, have a history of providing a form of attachment. This is not necessarily a conscious choice, but rather a deeply ingrained response to perceived needs for connection, even if those connections are ultimately unhealthy. The siren song of the familiar, even when it leads to troubled waters, can be difficult to resist. You are, in essence, chasing the dragon of connection, sometimes settling for a weaker, dimmer flame when the brighter one is out of reach.

Understanding the addictive nature of human attachment is not about stigmatizing connection, but rather about recognizing its profound influence on your life. By understanding the neurochemical underpinnings, the evolutionary drives, and the formation of individual attachment styles, you can begin to navigate your relational landscape with greater awareness and intention. This knowledge empowers you to build healthier connections, to break free from detrimental patterns, and to ultimately foster a more fulfilling and secure sense of belonging in the world.

WARNING: Your Empathy Is a Biological Glitch (And They Know It)

FAQs

What is the addiction mechanism in human attachment?

The addiction mechanism in human attachment refers to the way certain brain systems involved in addiction, such as the release of dopamine and activation of reward pathways, also play a role in forming and maintaining emotional bonds between people. This mechanism explains why attachment can feel compelling and difficult to break, similar to addictive behaviors.

How does dopamine influence human attachment?

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and reward. During attachment, dopamine is released in response to positive interactions with loved ones, reinforcing the desire to maintain close relationships. This neurochemical process creates feelings of happiness and motivates individuals to seek proximity and connection.

Can attachment be considered a form of addiction?

While attachment shares some neurobiological features with addiction, such as craving and withdrawal symptoms, it is not classified as a pathological addiction. Instead, attachment is a natural and essential process for human survival and social functioning, though it can sometimes lead to unhealthy dependency patterns.

What role do oxytocin and vasopressin play in attachment?

Oxytocin and vasopressin are hormones that facilitate bonding and social behaviors. Oxytocin, often called the “love hormone,” promotes trust and emotional connection, while vasopressin is linked to pair bonding and protective behaviors. Both contribute to the formation and maintenance of strong attachments.

How can understanding the addiction mechanism in attachment help in therapy?

Recognizing the addiction-like qualities of attachment can help therapists address issues such as codependency, attachment disorders, and relationship difficulties. By understanding the neurobiological underpinnings, therapeutic approaches can be tailored to help individuals develop healthier attachment patterns and manage emotional dependencies.