You embark on a journey into the intricate landscape of the human brain, specifically focusing on a complex interplay of activity that often underpins various psychological experiences: prefrontal hyperactivation and limbic hypoactivation. This neuronal dance, where one region gears into overdrive while another simmers down, offers a unique window into the brain’s regulatory mechanisms and their potential disruptions. As you delve into this topic, you will gain a deeper understanding of how these distinct patterns of neural activity shape your thoughts, emotions, and behaviors.

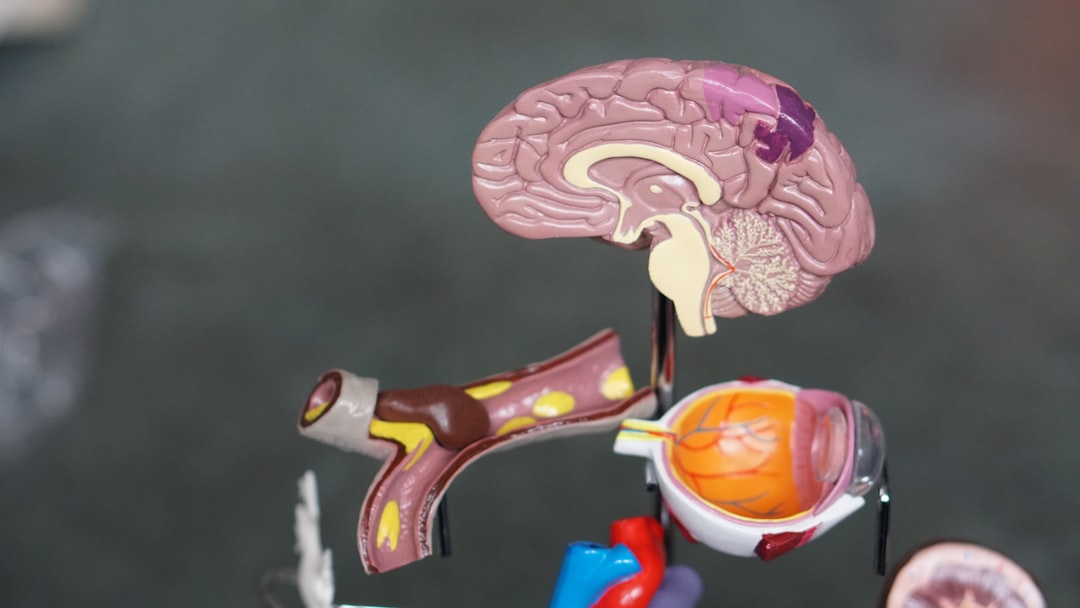

You perceive your brain not as a static entity, but as a symphony orchestra, where different sections – represented by distinct brain regions – play their parts in harmony, or at times, in discord. The prefrontal cortex (PFC), akin to the conductor, is responsible for executive functions, decision-making, working memory, and emotional regulation. Its highly developed circuitry allows you to plan your day, resist impulsive urges, and understand complex social cues. The limbic system, on the other hand, is the emotional core, the string section and percussion, generating fundamental feelings like fear, joy, anger, and pleasure. It includes structures like the amygdala, hippocampus, and cingulate gyrus, which are crucial for processing and storing emotional memories.

When you observe a healthy brain in action, you witness a delicate equilibrium. The PFC exerts top-down control over the limbic system, much like an experienced conductor guiding their musicians. This regulatory influence ensures that your emotional responses are appropriate to the situation, preventing overwhelming surges of feeling and promoting rational thought. This dynamic interplay is fundamental to your ability to navigate the complexities of life.

The Role of Executive Functions

Your prefrontal cortex is the seat of your executive functions. You rely on these functions daily to:

- Plan and organize: When you schedule your tasks or strategize for a project, your PFC is actively engaged.

- Prioritize and manage time: Sorting through urgent versus important matters is a PFC-driven process.

- Inhibit impulses: The ability to resist immediate gratification for a long-term goal is a hallmark of strong prefrontal control. You might, for instance, choose to study for an exam instead of watching a captivating show, thanks to your PFC.

- Regulate emotions: When you feel a surge of anger, your PFC helps you pause, reappraise the situation, and choose a more constructive response. You don’t immediately lash out; instead, you might take a deep breath or reconsider your reaction.

The Limbic System’s Emotional Core

The limbic system is the brain’s ancient emotional powerhouse, evolving to respond swiftly to threats and rewards. Its key components include:

- Amygdala: This almond-shaped structure is your brain’s alarm bell. It processes fear, anger, and other strong emotions, and is crucial for forming emotional memories. When you encounter a sudden danger, your amygdala triggers an immediate fight-or-flight response.

- Hippocampus: Essential for memory formation, particularly episodic memories and spatial navigation. It helps you recall the context of emotional events, allowing you to learn from past experiences. You remember where you parked your car, and also the emotional flavor of past events, like the joy of a graduation.

- Cingulate Gyrus: Involved in emotion formation and processing, learning, and memory. It helps you integrate emotional and cognitive information. You use it to understand the emotional significance of a situation and to regulate your responses.

The Feedback Loop: A Two-Way Street

You understand that the relationship between the PFC and the limbic system is not unidirectional. While the PFC exerts top-down control, the limbic system also sends signals back to the PFC, informing it of urgent emotional states. This creates a continuous feedback loop, constantly adjusting your internal state and behavioral output. Imagine your conductor getting feedback from the orchestra sections about their current state, allowing for subtle adjustments in tempo and dynamics.

Recent studies have highlighted the intriguing relationship between prefrontal hyperactivation and limbic hypoactivation, suggesting that this neural pattern may play a crucial role in emotional regulation and decision-making processes. For a deeper understanding of these concepts and their implications for mental health, you can explore a related article on this topic at Unplugged Psych. This resource provides valuable insights into how these brain activation patterns influence behavior and emotional responses.

Prefrontal Hyperactivation: The Overworked Conductor

When you consider prefrontal hyperactivation, you are observing a state where your PFC is working overtime, often excessively. This heightened activity can manifest in several ways, and while it might seem beneficial at first glance – a super-charged conductor, perhaps – it often signifies a disruption in the brain’s efficient functioning. It’s like a conductor who is constantly over-conducting, trying to control every minute detail, leading to rigidity and inflexibility.

Cognitive Rigidity and Over-Analysis

You might experience prefrontal hyperactivation as a tendency towards overthinking, rumination, and an inability to disengage from certain thought patterns. This can lead to:

- Perseveration: Getting stuck on a particular thought or action, even when it’s no longer productive. You might find yourself replaying a past conversation repeatedly, dissecting every word.

- Over-analysis: Breaking down situations into excessively small components, leading to decision paralysis. You spend hours researching the pros and cons of a simple purchase, unable to make a choice.

- Difficulty with cognitive flexibility: Struggling to adapt to new information or change perspectives. If your initial plan doesn’t work, you find it challenging to pivot to an alternative.

Excessive Self-Monitoring and Self-Criticism

Your PFC is heavily involved in self-monitoring. When it’s hyperactive, you might become overly self-aware and critical, leading to:

- Heightened self-consciousness: Feeling constantly observed and judged, even when no one is paying particular attention to you. You might meticulously check your appearance or second-guess your every action in social situations.

- Perfectionism and fear of failure: Setting impossibly high standards and experiencing intense anxiety about not meeting them. The fear of “getting it wrong” can paralyze you from taking action.

- Rumination on past mistakes: Replaying negative events and blaming yourself excessively. This can create a perpetual cycle of self-recrimination.

Top-Down Inhibition and Emotional Suppression

While the PFC’s role in emotional regulation is crucial, hyperactivation can lead to an over-zealous approach to emotional suppression. You might try to intellectualize your feelings or push them away, which can be counterproductive in the long run.

- Emotional numbing: A deliberate attempt to suppress emotional experiences, leading to a diminished capacity to feel both positive and negative emotions. You might feel emotionally flat or disconnected from your own inner world.

- Difficulty expressing emotions: Struggling to verbalize or outwardly convey your feelings, even with loved ones. You might keep your emotions bottled up, leading to internal pressure.

- Increased anxiety related to emotional expression: A fear of losing control or being overwhelmed by emotions if you allow yourself to feel them.

Limbic Hypoactivation: The Muted Orchestra

Simultaneously, you observe limbic hypoactivation, where the emotional core of the brain is operating at a reduced level. This is like the string section and percussion playing too softly, almost inaudibly, dulling the emotional richness of the performance. While some might initially perceive this as a calming effect, it often indicates a blunted emotional response and a disconnect from the inner affective experience.

Blunted Emotional Responses

When your limbic system is underactive, you might experience a significant reduction in the intensity and range of your emotions:

- Anhedonia: A diminished ability to experience pleasure from activities that were once enjoyable. Things that used to bring you joy, like a favorite hobby or spending time with friends, now feel flat or uninteresting.

- Emotional flatness: A general lack of emotional expressiveness and experience. You might feel apathetic or indifferent to situations that would normally evoke strong feelings in others.

- Difficulty recognizing and responding to others’ emotions: Struggling to empathize or connect emotionally with others, as your own emotional reference points are diminished. You might misinterpret social cues or appear emotionally distant.

Disconnection from Internal States

You might find yourself feeling detached from your own body and internal sensations. This can manifest as:

- Depersonalization: A feeling of detachment from your own self, as if you are observing yourself from outside your body. You might feel like a robot or an actor in your own life.

- Derealization: A feeling that the world around you is unreal or dreamlike. The environment might seem distorted or unfamiliar.

- Reduced interoception: A diminished awareness of your internal bodily states, such as heart rate, breathing, or hunger. You might miss important signals from your body, leading to a sense of disconnect.

Impaired Emotional Learning and Memory

The limbic system is crucial for forming emotional memories. When it’s hypoactivated, you might struggle to:

- Learn from emotionally salient experiences: The emotional “tag” associated with certain events is missing, making it difficult to remember their significance or modify future behavior accordingly. You might repeat mistakes because you haven’t fully processed the emotional consequences.

- Recall emotional memories: Even if you remember the factual details of an event, the emotional impact might be absent or significantly reduced. You remember attending a funeral, but the accompanying sadness is muted.

The Co-Occurrence: A Dysfunctional Duo

When prefrontal hyperactivation and limbic hypoactivation occur simultaneously, you witness a particularly challenging scenario. It’s like the conductor is frantically waving their baton, trying to control a section of the orchestra that is barely playing. This mismatch creates a system where executive control is over-exerted, yet the very emotions it seeks to regulate are muted or inaccessible.

The Anxious-Depressive Spectrum

You find that this pattern of brain activity is frequently observed in individuals experiencing conditions along the anxious-depressive spectrum. While the precise mechanisms are still under investigation, the theory suggests that:

- Anxiety: The hyperactive PFC contributes to persistent worry, rumination, and an amplified focus on potential threats. This incessant mental activity can be exhausting.

- Depression: The limbic hypoactivation contributes to emotional blunting, anhedonia, and a general lack of motivation. The joy and despair, the very colors of emotional life, become muted.

This combination can create a vicious cycle. The overactive PFC attempts to “think its way out” of the emotional void, but the lack of limbic feedback means there’s little genuine emotional “data” to process. This leads to a sense of intellectualizing emotions without truly feeling them, or a constant analytical loop without emotional resolution.

Maladaptive Coping Strategies

You might observe that individuals exhibiting this pattern often resort to maladaptive coping strategies as they try to manage their internal experience. These strategies, while providing temporary relief, can exacerbate the underlying imbalance:

- Avoidance: Disengaging from social situations or activities that might evoke strong emotions, further contributing to emotional isolation.

- Substance abuse: Using drugs or alcohol to numb overwhelming thoughts or emotional emptiness.

- Excessive work or distractions: Engaging in constant activity to avoid introspection or confronting uncomfortable feelings. You might throw yourself into your work, using it as a shield against your inner world.

Impaired Insight and Self-Compassion

The disconnect between the overly active cognitive functions and the blunted emotional experience can make it difficult for you to understand your own emotional states or offer yourself compassion.

- Difficulty identifying emotions: You may struggle to accurately label and understand what you are feeling, leading to a sense of confusion and frustration.

- Self-criticism intensification: The hyperactive PFC, in its analytical overdrive, can turn its critical gaze inward, exacerbating feelings of inadequacy and worthlessness.

- Reduced empathy for self: You might find it hard to be kind or understanding toward yourself, dismissing your own struggles as weaknesses.

Recent studies have explored the intriguing relationship between prefrontal hyperactivation and limbic hypoactivation, shedding light on how these neural dynamics influence emotional regulation and decision-making processes. For a deeper understanding of this topic, you can refer to a related article that discusses the implications of these brain activity patterns on mental health and behavior. This insightful piece can be found here, providing valuable information for those interested in the complexities of brain function.

Causes and Contributing Factors: Unraveling the Complexity

| Brain Region | Activation Pattern | Associated Function | Common Observations | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) | Hyperactivation | Executive functions, decision making, cognitive control | Increased blood flow and metabolic activity during cognitive tasks | May indicate compensatory mechanisms or increased cognitive effort |

| Amygdala (Limbic System) | Hypoactivation | Emotional processing, fear response, threat detection | Reduced activation in response to emotional stimuli | Associated with blunted emotional responses or impaired emotional regulation |

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) | Variable (often hypoactivation) | Error detection, emotional regulation, conflict monitoring | Decreased activation linked to emotional dysregulation | May contribute to difficulties in managing emotional responses |

| Functional Connectivity | Reduced PFC-limbic connectivity | Integration of cognitive and emotional processing | Lower synchronization between PFC and limbic regions | Impaired top-down regulation of emotions |

| Clinical Context | Observed in disorders such as | Depression, anxiety, PTSD, schizophrenia | Altered activation patterns during emotional and cognitive tasks | Potential target for therapeutic interventions |

You understand that the emergence of prefrontal hyperactivation and limbic hypoactivation is rarely attributable to a single cause. Instead, it arises from a complex interplay of genetic predispositions, environmental stressors, developmental experiences, and neurochemical imbalances.

Genetic Vulnerability

Research suggests that certain genetic markers can increase your susceptibility to conditions where this neural pattern is observed. These genes might influence the production or reuptake of neurotransmitters, the development of neural circuits, or the individual’s stress response. You might be predisposed to a more anxious temperament, for instance, due to inherited traits.

Early Life Stress and Trauma

Adverse early life experiences, such as childhood neglect, abuse, or chronic stress, can profoundly shape brain development. You are aware that these experiences can alter the wiring of critical brain regions, making you more prone to developing dysregulated emotional responses later in life. The developing brain is highly пластичный, meaning it is more susceptible to enduring changes.

- Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis Dysregulation: Chronic stress can disrupt the HPA axis, your body’s central stress response system, leading to sustained elevated cortisol levels. This can impact the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, contributing to the observed brain activity patterns.

- Altered Neurotransmitter Systems: Early trauma can lead to imbalances in neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, which play crucial roles in mood, motivation, and emotional regulation.

Chronic Stress and Burnout

In adulthood, prolonged exposure to high levels of stress, without adequate recovery, can also contribute to this neural pattern. You may experience chronic work-related stress, financial worries, or relationship difficulties, all of which tax your brain’s resources.

- Prefrontal Exhaustion: Constant engagement of executive functions under stress can lead to a state of “prefrontal exhaustion,” where the PFC attempts to maintain control but becomes less efficient, paradoxically leading to hyperactivation as it struggles to cope.

- Limbic System Desensitization: Continuous exposure to stressors can lead to a kind of desensitization in the limbic system, where it becomes less responsive to emotional stimuli as a protective mechanism.

Neurochemical Imbalances

You recognize that imbalances in various neurotransmitters are strongly implicated in the observed patterns.

- Serotonin: Critical for mood regulation, sleep, and appetite. Low levels are often associated with depression and emotional blunting.

- Dopamine: Involved in reward, motivation, and pleasure. Reduced dopamine activity can contribute to anhedonia and lack of drive.

- GABA: The primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, responsible for calming brain activity. Disruptions in GABA signaling can contribute to anxiety and overexcitation in certain regions.

Therapeutic Approaches and Interventions: Restoring Harmony

You understand that addressing prefrontal hyperactivation and limbic hypoactivation requires a multifaceted approach, aiming to restore the brain’s natural equilibrium. The goal is to help your “conductor” and “orchestra” find their rhythm once again.

Psychological Therapies

Several therapeutic modalities are highly effective in helping individuals manage and rebalance these neural patterns:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): This therapy helps you identify and challenge maladaptive thought patterns stemming from the hyperactive PFC. By reframing negative thoughts and developing healthier coping strategies, you can reduce rumination and excessive self-criticism. For instance, if you constantly worry about making mistakes, CBT helps you question the validity of those fears and develop more realistic self-expectations.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT): A form of CBT that emphasizes emotional regulation, mindfulness, and distress tolerance. DBT skills help you acknowledge and process emotions without being overwhelmed, fostering a healthier relationship with your limbic system. You learn to observe your emotions without judgment and to choose constructive responses rather than impulsive ones.

- Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR): Mindfulness practices train you to notice thoughts and feelings without judgment, allowing the hyperactive PFC to quiet down and the limbic system to register emotions more clearly. By focusing on the present moment, you can reduce rumination and increase emotional awareness.

- Schema Therapy: This approach addresses deeply ingrained maladaptive patterns (schemas) that often originate in early life. By understanding and challenging these core beliefs, you can begin to heal the emotional wounds that contribute to the imbalance.

Pharmacological Interventions

For some individuals, medication can play a crucial role in rebalancing neurochemical systems and alleviating symptoms. You recognize that these are often used in conjunction with therapy.

- Antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs): These medications work by increasing the availability of neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinephrine in the brain, which can help to reduce limbic hypoactivation and improve mood.

- Anxiolytics: These medications can help to reduce acute anxiety and calm the overactive prefrontal cortex, providing temporary relief, though long-term use often requires careful consideration.

Lifestyle Modifications

You have a significant role to play in supporting your brain health through conscious lifestyle choices. These interventions can complement formal therapy and medication:

- Regular Exercise: Physical activity has profound effects on brain chemistry, promoting neurogenesis, reducing stress hormones, and improving mood. It can help to quiet the hyperactive PFC and re-engage the limbic system in a healthy way.

- Balanced Nutrition: A diet rich in whole foods, omega-3 fatty acids, and antioxidants supports brain function and neurotransmitter production. Limiting processed foods and excessive sugar can stabilize mood and energy levels.

- Sufficient Sleep: Adequate sleep is essential for brain repair, memory consolidation, and emotional regulation. Sleep deprivation can exacerbate both prefrontal hyperactivation (leading to poorer decision-making) and limbic dysregulation (leading to increased emotional reactivity).

- Stress Management Techniques: Incorporating practices like yoga, meditation, deep breathing exercises, or spending time in nature can help you regulate your stress response and restore balance between your prefrontal cortex and limbic system. These techniques help to downregulate the stress response and provide a sense of calm. You learn to actively engage your parasympathetic nervous system, countering the effects of chronic stress.

- Social Connection: Strong social bonds act as a buffer against stress and promote emotional well-being. Connecting with others can provide emotional support and a sense of belonging, which is crucial for reducing feelings of isolation and anhedonia.

Ultimately, by understanding the complex interplay of prefrontal hyperactivation and limbic hypoactivation, you empower yourself with knowledge. This knowledge is a compass, guiding you towards interventions and practices that can help your brain orchestra find its harmonious rhythm once again, allowing you to experience a fuller spectrum of thoughts, emotions, and a greater sense of well-being.

WARNING: Your Empathy Is a Biological Glitch (And They Know It)

FAQs

What is prefrontal hyperactivation?

Prefrontal hyperactivation refers to an increased level of activity in the prefrontal cortex, a brain region involved in complex cognitive functions such as decision-making, attention, and executive control.

What does limbic hypoactivation mean?

Limbic hypoactivation describes reduced activity in the limbic system, which includes structures like the amygdala and hippocampus that are critical for emotion regulation, memory, and motivation.

How are prefrontal hyperactivation and limbic hypoactivation related?

These two phenomena often occur together in certain neurological or psychiatric conditions, where increased prefrontal activity may compensate for or contribute to decreased limbic system responsiveness, affecting emotional processing and regulation.

In which conditions are prefrontal hyperactivation and limbic hypoactivation commonly observed?

They are commonly observed in disorders such as depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), where altered brain activity patterns impact mood and cognitive function.

How are prefrontal hyperactivation and limbic hypoactivation measured?

These brain activity patterns are typically measured using neuroimaging techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) or positron emission tomography (PET), which track changes in blood flow or metabolic activity in specific brain regions.