You, as an empath, frequently find yourself navigating a complex internal landscape, one where your profound capacity for understanding and sharing the feelings of others often collides with your personal boundaries. This internal conflict manifests most acutely when faced with the necessity of refusing a request or declining an invitation. The act of saying “no,” which for many is a simple assertion of self, becomes for you a nuanced and often agonizing decision, laden with the perceived burden of potential distress you might inflict upon another. This inherent difficulty in setting limits is a defining characteristic of your empathic nature, and understanding its roots is crucial for your well-being.

Your empathetic capacity, while a powerful gift that allows you to connect deeply and offer profound support, simultaneously presents a significant challenge when it comes to self-preservation. You absorb the emotional cues of others with an almost visceral intensity, processing their feelings not merely as information but as personal experiences. This makes the act of refusal inherently difficult, as you anticipate and internalize the potential negative repercussions of your “no” on the other person.

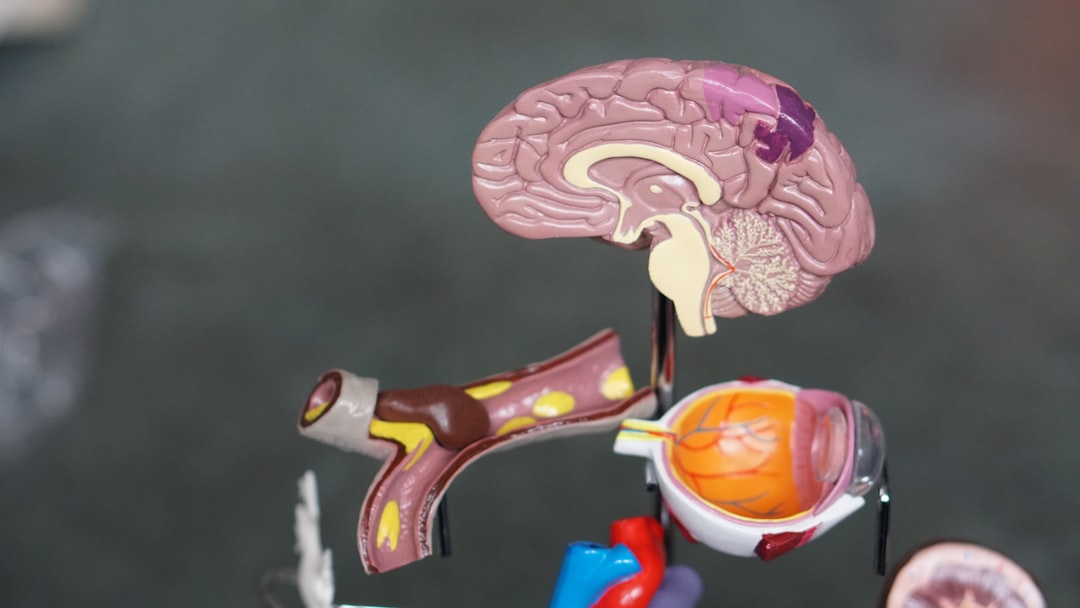

The Mirror Neuron System and Emotional Resonance

From a neurological perspective, your heightened empathy may be partly attributed to a highly active mirror neuron system. This network of brain cells is responsible for understanding and imitating the actions and intentions of others, effectively allowing you to “mirror” their experiences. When you witness someone expressing a need or desire, your mirror neurons fire, creating an internal simulation of their emotional state. This means that a request, even if inconvenient or inappropriate for you, can trigger a sympathetic resonance within your own emotional landscape, making it difficult to disengage without feeling a residual sense of conflict. You are, in essence, experiencing a diluted version of their potential disappointment or frustration, even before it manifests.

The Burden of Anticipation

Your empathic nature extends beyond merely processing current emotions; you also possess a remarkable capacity for anticipating future emotional states. When someone presents you with a request, you don’t just hear the words; you project yourself into their potential reaction if you were to decline. You might visualize their disappointment, their hurt, or even their sense of abandonment. This pre-emptive empathy can be a significant motivator in acceding to requests that you might otherwise refuse, as you actively seek to prevent these negative emotional outcomes. This anticipatory burden can be an exhausting mental exercise, draining your emotional reserves before a decision is even made.

Many empaths struggle with the feeling of guilt when it comes to saying no, often stemming from their deep sensitivity to the emotions of others. This phenomenon is explored in detail in the article “Understanding Empath Guilt” on Unplugged Psych, which discusses the psychological reasons behind this guilt and offers strategies for setting healthy boundaries. For more insights on this topic, you can read the article here: Understanding Empath Guilt.

The Social Contract and the Empath’s Role

Human societies are built upon intricate webs of social contracts, both explicit and implicit, that govern interactions and expectations. As an empath, you often internalize these contracts with a heightened sense of responsibility, feeling a greater personal obligation to uphold them, particularly when they involve providing support or assistance.

The Implicit Expectation of Help

You frequently encounter the unstated societal expectation that a “good” person will always be helpful, accommodating, and agreeable. This expectation, while a general precept, feels particularly weighty to you due to your acute sensitivity to social nuances. You may perceive that saying “no” is a direct violation of this implicit contract, potentially leading to social disapproval or a diminished perception of your character. This fear of being judged as unhelpful or uncaring can be a powerful disincentive to assert your boundaries.

The “Fixer” Archetype

You may also find yourself unconsciously cast in the role of the “fixer” or the “helper” within your social circles. Others, sensing your innate capacity for empathy and willingness to assist, may gravitate towards you with their problems and needs. While this can be a validating experience, it can also create an almost magnetic pull towards taking on responsibilities that are not yours. Your internal programming as a problem-solver, combined with external reinforcement, can make it exceptionally challenging to deviate from this ingrained role, even when it leads to your own burnout.

The Internal Conflict: Self-Preservation vs. Altruism

At the heart of your struggle with saying “no” lies a fundamental conflict between your innate drive to alleviate suffering and your equally vital need for self-preservation. This is not a simple ethical dilemma; it is a profound internal battle that can leave you feeling torn and depleted.

The Exhaustion of Unlimited Giving

You understand, often intimately, the concept of emotional reserves. Like a well, your capacity for giving is not infinite. When you consistently say “yes” to requests that drain your energy, compromise your time, or infringe upon your personal space, you are effectively depleting this well. The initial intention to help, born of genuine compassion, can quickly transform into resentment, exhaustion, and even a sense of being exploited. This internal conflict between wanting to help and feeling overwhelmed is a common experience for you.

The Erosion of Boundaries

Your difficulty in saying “no” often manifests as a porousness in your personal boundaries. You may find yourself agreeing to commitments you regret, sacrificing your own needs for the sake of others, or allowing others to impinge on your time and energy. This erosion of boundaries is a gradual process, but its long-term effects can be significant, leading to feelings of being unseen, unheard, and ultimately, unable to fully function at your optimal level. Reclaiming and fortifying these boundaries is an essential step towards self-care.

The Cognitive Distortions of Empathic Guilt

Your empathic tendencies, while valuable, can sometimes lead to cognitive distortions—patterns of thinking that are irrational or exaggerated and contribute to your feelings of guilt when setting boundaries. Recognizing these distortions is the first step towards challenging them.

Catastrophizing the “No”

You may frequently engage in catastrophizing, where you predict the most extreme and negative possible outcomes of your refusal. For instance, declining a request might escalate in your mind to the severing of a friendship, the collapse of a mutual project, or even the complete ruin of the other person’s day. While empathy allows you to imagine potential negative feelings, catastrophizing amplifies these possibilities to an unrealistic degree, rendering the act of saying “no” an insurmountable obstacle.

The “Perceived Obligation” Fallacy

You may operate under the fallacy that if someone asks you for something, you are inherently obligated to provide it, particularly if you believe you possess the capacity to do so. This perceived obligation is often self-imposed, arising from your desire to be helpful and avoid causing discomfort. However, true obligation rests on mutual agreement and respect for individual autonomy, not solely on the initiation of a request. Challenging this fallacy means recognizing that your capacity to help does not automatically translate into an obligation to do so.

Personalizing Others’ Feelings

You often have a tendency to personalize the feelings of others, believing that their emotional state is a direct consequence of your actions, even when it is not. If someone expresses disappointment upon hearing your “no,” you may internalize this disappointment as a personal failing, rather than acknowledging it as a legitimate, though perhaps inconvenient, emotional response that is ultimately their own to manage. This personalization fuels your guilt, creating a direct link between your refusal and their perceived suffering.

Many empaths struggle with the feeling of guilt when it comes to saying no, often stemming from their deep sensitivity to the emotions of others. This tendency can lead to a cycle of overcommitment and emotional exhaustion. For a deeper understanding of this phenomenon, you can explore a related article that discusses the psychological aspects of empathy and boundaries. It offers valuable insights into why empaths often prioritize others’ needs over their own. To read more, check out this informative piece on the topic at Unplugged Psych.

Strategies for Cultivating a Healthier “No”

| Reason | Description | Impact on Empaths | Common Emotional Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Sensitivity to Others’ Emotions | Empaths deeply feel others’ emotions, making it hard to disappoint or upset them. | Leads to difficulty in setting boundaries. | Guilt and anxiety when saying no. |

| Desire to Help and Support | Strong urge to assist others even at personal cost. | Reluctance to refuse requests. | Feeling selfish or uncaring when declining. |

| Fear of Conflict or Rejection | Worry that saying no will cause tension or loss of relationships. | Avoidance of saying no to maintain harmony. | Guilt mixed with fear and stress. |

| Internalized Beliefs About Self-Worth | Belief that self-worth is tied to pleasing others. | Difficulty prioritizing own needs. | Guilt and self-criticism when asserting boundaries. |

| Lack of Practice in Boundary Setting | Limited experience or skills in saying no effectively. | Increased feelings of overwhelm and guilt. | Confusion and self-doubt. |

Learning to say “no” as an empath is not about becoming less empathetic; it’s about becoming more strategically empathetic, focusing your energy where it is most genuinely beneficial, both for yourself and for those around you. This requires intentional practice and a re-evaluation of your internal narratives.

Prioritizing Your Own Well-being

You must first recognize that your own well-being is not selfish; it is foundational to your ability to genuinely help others. An empty well cannot provide water. Just as a flight attendant instructs you to put on your own oxygen mask before assisting others, you must prioritize your own emotional and energetic needs. This means consciously scheduling time for rest, hobbies, and activities that replenish your spirit, and viewing these as non-negotiable commitments. When a request conflicts with these priorities, a “no” becomes a necessary act of self-preservation.

The Power of the “Gracious No”

Saying “no” does not have to be abrupt or uncaring. You can practice delivering a “gracious no” that acknowledges the other person’s request while firmly asserting your boundary. This might involve expressing regret, explaining your limitations briefly (without over-explaining or justifying excessively), and perhaps offering an alternative solution if appropriate and genuinely feasible. For example, “I appreciate you thinking of me for this, but unfortunately, I’m stretched thin right now and won’t be able to commit. I hope it goes well!” This approach allows you to maintain your empathic connection while protecting your boundaries.

Practicing Assertive Communication

You can develop and refine your skills in assertive communication. This involves clearly and directly expressing your needs and boundaries without being aggressive or passive. It means using “I” statements to articulate your capacity and limitations. For instance, instead of “I can’t possibly do that,” try “I need to prioritize X right now, so I won’t be able to help with Y.” Assertiveness is a learned skill, and like any skill, it improves with practice. Start with smaller, less emotionally charged situations to build your confidence.

Understanding Emotional Responsibility

It is crucial for you to internalize the concept of emotional responsibility. While your empathy allows you to understand the feelings of others, you are not responsible for their emotional responses to your decisions, especially when those decisions are made in your best interest. People are responsible for managing their own feelings. Your “no” may trigger disappointment, but that disappointment is theirs to process, not yours to absorb and alleviate at your own expense. This distinction is vital for detaching from unnecessary guilt.

Setting Pre-emptive Boundaries

You can proactively establish boundaries before requests are even made. This might involve communicating your availability, declaring certain times as unavailable, or making it known that you are not taking on extra commitments. Setting pre-emptive boundaries can reduce the frequency with which you are put in a position to say “no,” thereby mitigating the associated guilt. For instance, if you have a regular day for personal appointments, you might communicate, “Tuesdays are my designated day for personal tasks, so I won’t be available then.” This clarifies your limitations before a specific request arises.

By recognizing the unique challenges your empathic nature presents in the act of refusal, and by actively implementing these strategies, you can transition from a cycle of guilt and depletion to one of self-awareness and sustainable, genuinely impactful kindness. Your empathy is a profound strength, and learning to protect it is the ultimate act of compassion for yourself and, paradoxically, for those you are best equipped to support.

WARNING: Your Empathy Is a Biological Glitch (And They Know It)

FAQs

What does it mean to be an empath?

An empath is a person who has a heightened ability to sense and understand the emotions and feelings of others. They often absorb others’ emotional states, which can deeply affect their own mood and well-being.

Why do empaths often feel guilty when saying no?

Empaths tend to feel guilty saying no because they are highly sensitive to others’ needs and emotions. They may worry about disappointing or hurting someone, leading to feelings of guilt when they set boundaries or decline requests.

How does guilt impact an empath’s ability to set boundaries?

Guilt can make it difficult for empaths to establish and maintain healthy boundaries. They may prioritize others’ feelings over their own needs, resulting in overcommitment, stress, and emotional exhaustion.

Can empaths learn to say no without feeling guilty?

Yes, empaths can develop strategies to say no assertively while managing guilt. This includes practicing self-awareness, understanding the importance of boundaries, and recognizing that saying no is a form of self-care rather than selfishness.

What are some common signs that an empath is struggling with guilt over saying no?

Signs include over-apologizing, feeling anxious or stressed after declining requests, difficulty asserting personal needs, and a tendency to overextend themselves to avoid disappointing others.