When life feels like a runaway train, derailing your sense of normalcy and leaving you adrift in a sea of thoughts and sensations, grounding techniques can be your anchor. You might find yourself experiencing moments of intense anxiety, dissociation, or overwhelming emotions that pull you away from the present reality. These moments can be disorienting, making it difficult to focus, think clearly, or feel safe. Grounding is not about suppressing these experiences, but rather about gently bringing yourself back to the tangible world, the here and now. It’s about noticing the solid ground beneath your feet, the air you breathe, and the sensations in your body, offering a steadying presence when your internal world feels chaotic.

You are likely seeking grounding techniques because you have encountered situations where your perception of reality has become fragmented or distorted. These experiences can manifest in various ways, but they all share a common thread: a disconnect from the present moment and the physical world.

The Nature of Disconnection

Disconnection from reality, often referred to as dissociation, can be a coping mechanism for your mind when faced with overwhelming stress, trauma, or intense emotions. It is as if your consciousness decides to unmoor itself from the ship of your body, leaving you to bob on the surface while your internal storm rages below. This can make you feel detached from your body, your surroundings, or even your sense of self. You may feel like you are watching yourself from a distance, or that the world around you is unreal, blurry, or dreamlike. Tasks you normally perform with ease can suddenly feel foreign and difficult.

Triggers for Disconnection

Various factors can trigger these feelings of disconnection. For some, it might be a return to a place or situation that reminds them of a past trauma. For others, it could be a surge of intense anxiety, a panic attack, or even extreme fatigue. The feeling of being overwhelmed, whether by external circumstances or internal emotional turmoil, can act as a switch, prompting your mind to create a protective distance. Think of it like a thermostat that malfunctions and suddenly cranks up the heat to an unbearable level; dissociation can be your system’s attempt to create a buffer zone, however uncomfortable.

The Role of Sensory Input

Our senses are the primary conduits through which we experience reality. When you are feeling disconnected, your sensory input might be dulled, distorted, or even ignored. Grounding techniques work by actively engaging your senses, intentionally drawing your attention to what you can see, hear, smell, touch, and taste. This deliberate focus on sensory information can act as a gentle but firm hand, guiding your attention back to the present physical experience. It’s like tuning an old radio, searching for a clear station amidst the static and interference of overwhelming thoughts.

Tactile anchors play a crucial role in helping individuals re-integrate into reality, especially for those experiencing dissociation or overwhelming emotions. A related article that delves deeper into this topic can be found at Unplugged Psych, where various therapeutic techniques, including the use of tactile anchors, are explored to enhance grounding and mindfulness practices. This resource provides valuable insights into how physical sensations can effectively bridge the gap between one’s internal experiences and the external world.

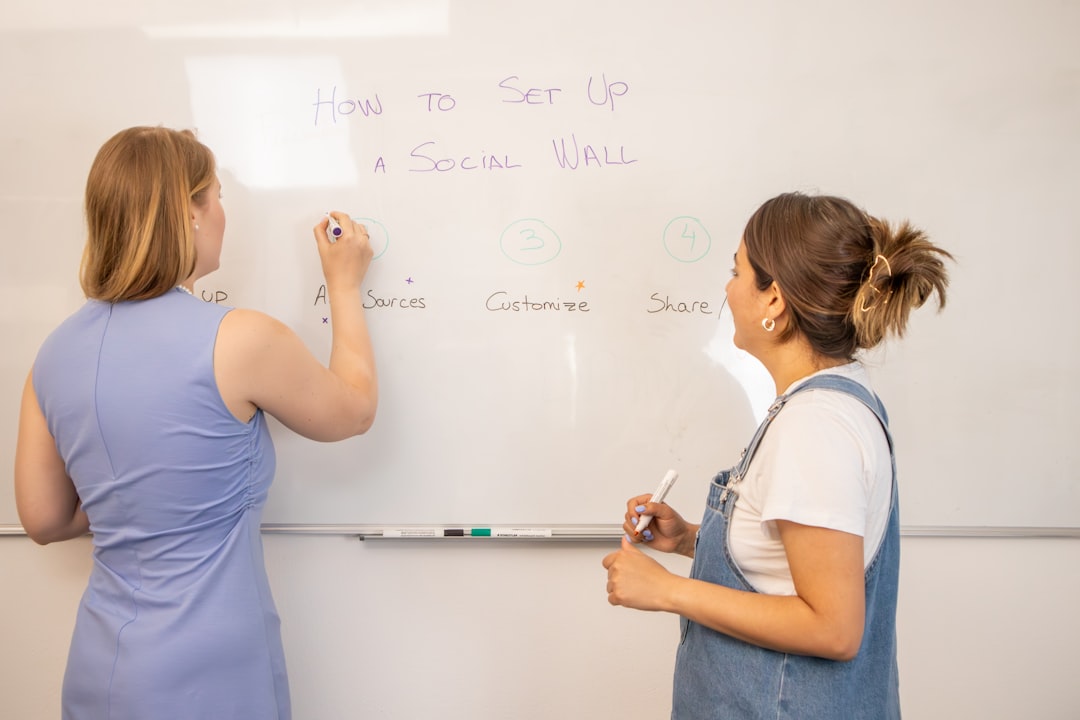

Categories of Grounding Techniques

Grounding techniques can be broadly categorized based on the senses they engage and the approach they take. Understanding these categories can help you identify which techniques might be most effective for you in different situations.

Sensory Grounding Techniques

These techniques directly involve your five senses, using them as anchors to the present. They are often the most immediate and accessible forms of grounding.

Visual Grounding

This involves actively observing your surroundings and noticing details. You might consciously look around a room and identify five things you can see, then four things you can touch, then three you can hear, and so on.

- The “5-4-3-2-1” Method: This is a widely recognized and effective visual (and multi-sensory) grounding exercise. You systematically bring your awareness to your environment by identifying:

- 5 things you can see: Look for colors, shapes, textures, objects, or anything that captures your visual attention. For instance, you might notice the pattern on a rug, the dust motes in a sunbeam, the color of a book cover, the shape of a window frame, or the way light reflects off a surface.

- 4 things you can touch/feel: Focus on the physical sensations. Feel the texture of your clothing against your skin, the floor beneath your feet, the smooth surface of a table, the roughness of a wall, or the warmth of your own hands.

- 3 things you can hear: Listen to the sounds around you, both near and far. Notice the hum of appliances, the rustle of leaves outside, distant traffic, the sound of your own breathing, or even the subtle clicks and squeaks of your environment.

- 2 things you can smell: Take a moment to consciously inhale and identify any scents. This might be the faint aroma of coffee, the fragrance of a candle, the smell of the air, or even just the neutral scent of your surroundings. If you’re struggling to find distinct smells, you can bring something with a known scent closer, like a piece of fruit or a scented lotion.

- 1 thing you can taste: You might focus on the lingering taste in your mouth, or deliberately take a sip of water, chew a piece of gum, or eat a small, flavorful item. Pay attention to the flavor, texture, and temperature.

- Descriptive Observation: Simply describe your surroundings in detail, either internally or out loud. Focus on specific attributes of objects. For example: “This is a wooden chair. The wood is a dark brown. I can see the grain of the wood. It has four legs. There is a slight scratch on the left leg.” This active engagement with visual information forces your brain to focus on external stimuli.

Auditory Grounding

This involves actively listening to sounds in your environment.

- Sound Mapping: Close your eyes and try to identify as many distinct sounds as possible. Try to determine where each sound is coming from and its approximate distance. This can help you reorient yourself to your physical location.

- Listening to Music: Choose music that is calming and consistent, without sudden changes in tempo or volume. Focus on the individual instruments, the melody, or the rhythm. Avoid music with lyrics that might distract you or trigger unwanted thoughts.

- Focusing on Your Own Sounds: Pay attention to the sound of your own breathing, your heartbeat, or even the sound of your feet hitting the ground as you walk. These are constant, present sounds that can be comforting.

Tactile Grounding

This involves focusing on physical sensations through touch.

- Holding an Object: Select an object with an interesting texture – a smooth stone, a piece of fabric, a cool metal object. Focus on how it feels in your hands. Notice its weight, temperature, and surface properties.

- Temperature Contrast: You can use temperature to ground yourself. For instance, holding an ice cube or a warm mug can provide a distinct sensory experience. You can also feel the temperature of the air on your skin or the coolness of a wall.

- Skin Sensations: Gently run your fingers over different parts of your body, noticing the texture of your skin, the feeling of your clothes, or the pressure of your feet on the floor. You can also try pressing your palms together firmly and noticing the sensation.

Olfactory and Gustatory Grounding

These techniques focus on smell and taste.

- Smelling: Keep a small vial of a pleasant-smelling essential oil (like lavender or peppermint) or a strongly scented item (like a piece of citrus peel) on hand. When you feel disconnected, take a few deep breaths and focus on the scent.

- Tasting: This can involve eating or drinking something with a strong, distinct flavor. Think of biting into a juicy piece of fruit, sucking on a flavored candy, or drinking a glass of strong tea. Pay attention to the flavor, the texture, and the sensation in your mouth.

Cognitive Grounding Techniques

These techniques use your thinking processes to bring your attention back to the present. They are about actively engaging your mind in a way that anchors you to reality.

Mental Engagement Techniques

These exercises require focused mental effort, redirecting your cognitive resources away from internal distress.

- Describing Your Surroundings (Internal): Similar to visual grounding, you can mentally describe your environment in detail without necessarily speaking aloud. Focus on colors, shapes, textures, and the spatial relationships between objects.

- Naming Objects: Look around and systematically name all the objects you see. This simple act of verbalization (internal or external) requires cognitive processing and brings your focus to the external world.

- Reciting Information: You can recite things you know well by heart, such as the alphabet, the days of the week, the months of the year, or even a favorite poem or song lyrics. The familiarity and structure of this information can be grounding.

- Mental Math: Perform simple calculations in your head. This requires focused attention and can be a distraction from intrusive thoughts.

Reality Testing

This involves consciously questioning and affirming your perception of reality.

- Asking Yourself Questions: Ask yourself questions like: “Where am I?” “What day is it?” “What am I doing right now?” “Who am I with?” Answering these questions factually can reinforce your connection to your current reality.

- Challenging Unrealistic Thoughts: When you experience thoughts that feel detached from reality, you can gently challenge them. For example, if you think, “Everything is blurry,” you can counter with, “No, the edges of the table are sharp, and I can see the individual threads in my shirt.”

Physical Grounding Techniques

These techniques involve using your body and physical movement to re-establish a connection with yourself and your environment.

Movement-Based Techniques

These involve deliberate physical actions.

- Walking: Go for a walk, focusing on the sensation of your feet hitting the ground, the movement of your legs, and the rhythm of your steps. Pay attention to the sights and sounds you encounter on your walk.

- Stretching: Perform simple stretches, focusing on the sensations in your muscles. Notice how your body feels as you move and lengthen.

- Tensing and Releasing Muscles: You can go through your body, tensing each muscle group for a few seconds and then releasing it, paying attention to the physical sensation of release. This can help you become more aware of your body.

Breath-Focused Techniques

Your breath is a constant physical process that can serve as a powerful grounding tool.

- Deep Breathing: Inhale slowly and deeply through your nose, filling your lungs. Hold your breath for a moment, and then exhale slowly through your mouth. Focus on the sensation of the air entering and leaving your body.

- Counting Breaths: Count your breaths as you inhale and exhale. This simple counting exercise can provide a manageable focus for your attention.

- Observing Your Breath: Simply pay attention to the natural rhythm of your breathing without trying to change it. Notice the rise and fall of your chest or abdomen.

Implementing Grounding Techniques

Knowing about grounding techniques is the first step; effectively using them requires practice and self-awareness. It’s not a one-size-fits-all solution, and what works for one person might not work for another, or even for the same person in different situations.

Identifying Your Personal Triggers

The more you understand what causes you to feel disconnected, the better equipped you will be to intervene early. Keep a journal if that helps you to track patterns in your thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

- Situational Triggers: Are there specific places, social situations, or times of day that tend to precede feelings of disconnection? Noticing these patterns can allow you to prepare or to have your grounding tools ready.

- Emotional Triggers: Are certain emotions like intense fear, sadness, or anger more likely to lead to disconnection? Understanding your emotional landscape is crucial.

- Physical Triggers: Fatigue, hunger, or certain sensory stimuli can sometimes play a role.

Practicing Regularly

Grounding techniques are most effective when they are practiced regularly, not just during moments of crisis. Think of it like training for a marathon; you wouldn’t wait until race day to start running.

- Daily Practice: Integrate brief grounding exercises into your daily routine. This could be a few minutes of deep breathing in the morning, a sensory observation during your lunch break, or a brief tactile exercise before bed.

- Pre-emptive Practice: If you know you will be entering a potentially triggering situation, practice your grounding techniques beforehand. This can build your resilience and make them more accessible when you need them.

Choosing the Right Technique for the Moment

The effectiveness of a grounding technique can depend on the intensity of your experience and your immediate environment.

- For Mild Disconnection: A simple sensory observation, like the 5-4-3-2-1 method, might be sufficient.

- For More Intense Disconnection: You might need to engage more actively with physical or cognitive techniques, like walking or reciting information.

- Consider Your Environment: If you are in a crowded public place, auditory techniques might be challenging. Tactile or visual techniques might be more discreet and effective.

Being Patient and Kind to Yourself

It is important to approach grounding with patience and self-compassion. You are learning a new skill, and there will be times when it feels more difficult or less effective.

- Avoid Self-Criticism: If a technique doesn’t work immediately, do not get discouraged. It is a process.

- Experimentation: Be willing to try different techniques and combinations to discover what works best for you. Your needs may change over time.

When Grounding May Be More Challenging

While grounding techniques are generally beneficial, there are specific situations and conditions where they might prove more challenging or require a more nuanced approach.

Dissociative Disorders

For individuals with diagnosed dissociative disorders, such as Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) or Dissociative Amnesia, grounding techniques are a crucial part of management but may need to be implemented with greater care and often under the guidance of a mental health professional.

- The Nature of Dissociation in Disorders: In these conditions, dissociation is a more pervasive and deeply ingrained coping mechanism. The feeling of disconnection can be more intense, prolonged, and accompanied by significant identity disruption.

- Therapeutic Application: Grounding is often taught as a primary skill to help individuals maintain a connection to the present moment, reduce distress associated with flashbacks or alters, and improve overall functioning. However, the approach needs to be tailored to the individual’s specific experiences and level of functioning.

- Potential for Overwhelm: While intended to help, certain overwhelming sensory inputs or intense cognitive exercises could, in some rare cases, inadvertently trigger a more profound dissociative experience if not approached thoughtfully.

Severe Anxiety and Panic Attacks

During a severe anxiety or panic attack, your system is in a heightened state of alarm. While grounding is highly recommended, your ability to implement it can be hampered by the intensity of your symptoms.

- The “Fight or Flight” Response: When your body is flooded with adrenaline, focusing on external reality can feel like an immense effort. Your brain is preoccupied with perceived threats.

- Gradual Implementation: It may be more effective to start with simpler, more immediate grounding techniques, such as focusing on your breath or holding a comforting object, and gradually move to more complex ones as your anxiety subsides.

- The Goal of Stabilization: The primary goal during an acute attack is to achieve a sense of stabilization. It’s about gently nudging your awareness back, not forcing it.

Trauma Survivors

For individuals with a history of trauma, certain sensory stimuli or cognitive exercises might unintentionally trigger memories or somatic responses related to the trauma.

- The Body’s Memory: Trauma can create a deep imprint on the nervous system, and some sensory experiences that are grounding for others might activate a trauma response (e.g., a sudden loud noise, a specific smell).

- Gentle and Controlled Approach: It is often advised to approach grounding techniques with caution and to be highly attuned to your body’s signals. If a technique evokes distress, it is important to stop or modify it.

- Prioritizing Safety: The most crucial aspect is to ensure that grounding techniques create a sense of safety and do not inadvertently re-traumatize. Working with a trauma-informed therapist can provide guidance on safe and effective grounding strategies.

Neurological Conditions Affecting Sensory Processing

In some cases, underlying neurological conditions might affect how an individual processes sensory information, making them more or less responsive to certain grounding techniques.

- Sensory Sensitivities: Individuals with conditions like Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) may have heightened or diminished responses to sensory input. A technique that is grounding for one person might be overwhelming or ineffective for another with different sensory profiles.

- Tailoring Techniques: For example, a person with heightened sensitivity to sound might find loud music or the 5-4-3-2-1 method focusing on auditory input to be distressing. They might benefit more from tactile techniques using a specific texture or visual techniques focusing on calming, predictable patterns.

- Collaboration with Professionals: For individuals with these conditions, collaboration with occupational therapists or other specialists can be invaluable in identifying personalized and effective grounding strategies.

Tactile anchors play a significant role in helping individuals re-integrate into reality, especially for those experiencing dissociation or anxiety. By engaging the senses through physical objects, individuals can ground themselves in the present moment. For further insights on this topic, you may find it helpful to explore a related article that discusses various techniques for enhancing mindfulness and presence. You can read more about these strategies in this informative piece on Unplugged Psych.

The Long-Term Benefits of Grounding

| Metric | Description | Measurement Method | Typical Values | Relevance to Tactile Anchors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure Sensitivity | Ability to detect varying levels of pressure applied to the skin | Semmes-Weinstein monofilament test | 0.07g to 300g force | Determines effectiveness of tactile anchors in providing sensory feedback |

| Vibration Detection Threshold | Minimum vibration amplitude perceivable by the skin | Biothesiometer or tuning fork test | 5 to 50 microns at 100 Hz | Helps in designing tactile anchors that use vibration for reality re-integration |

| Spatial Resolution | Minimum distance between two points that can be perceived as separate | Two-point discrimination test | 2 to 5 mm on fingertips | Important for placement and size of tactile anchors |

| Response Time | Time taken for tactile sensation to be perceived after stimulus | Neurophysiological measurement | 20 to 50 ms | Critical for real-time feedback in re-integrating reality |

| Skin Conductance | Electrical conductance of skin, indicating sweat gland activity | Galvanic skin response sensor | 0.5 to 20 microsiemens | Can be used to monitor emotional state during tactile anchoring |

| Comfort Level | Subjective rating of comfort when using tactile anchors | User surveys and questionnaires | Scale of 1 (uncomfortable) to 10 (very comfortable) | Ensures long-term usability of tactile anchors |

Regularly employing grounding techniques can lead to significant improvements in your overall well-being and your capacity to navigate life’s challenges. These are not just temporary fixes; they are tools that, with consistent use, can reshape your relationship with your internal experiences and the external world.

Increased Self-Awareness

As you practice grounding, you inevitably become more attuned to your own internal states. You begin to notice the subtle shifts in your emotions, thoughts, and bodily sensations that precede periods of disconnection.

- Early Warning System: This increased awareness acts as an early warning system, allowing you to recognize signs of impending disconnection or distress before they become overwhelming. It’s like learning to read the barometer of your own mind and body, understanding when a storm might be brewing.

- Understanding Your Patterns: You develop a deeper understanding of your personal triggers and how your mind and body respond to stress. This self-knowledge is foundational for effective self-management.

Enhanced Emotional Regulation

Grounding techniques provide you with a tangible way to interrupt overwhelming emotional spirals. By anchoring yourself in the present, you create space between the intense emotion and your reaction to it.

- Interrupting the Cycle: Instead of being swept away by a wave of emotion, you can use grounding to regain your footing. This creates a crucial pause, allowing you to choose a more adaptive response rather than an impulsive one.

- Reducing Intensity: While grounding doesn’t eliminate emotions, it can significantly reduce their intensity and the feeling of being consumed by them. It’s like turning down the volume on an alarm that has gone off too loudly.

Improved Focus and Concentration

When your mind is scattered or detached, concentration becomes a significant challenge. Grounding techniques, by drawing your attention to the present, can help to sharpen your focus.

- Redirecting Attention: These techniques are essentially exercises in attention training. They teach your mind to return to the task at hand, whether that is a conversation, a work project, or simply experiencing the present moment.

- Greater Cognitive Clarity: By reducing the internal noise and distraction associated with disconnection, grounding can lead to clearer thinking and improved problem-solving abilities.

Greater Sense of Control and Agency

Feeling disconnected can often lead to a profound sense of powerlessness. Grounding techniques empower you by providing you with active strategies to influence your own state.

- Taking Back the Reins: You are no longer a passive observer being tossed about by internal chaos. You have tools to actively steer yourself back to a sense of stability and control.

- Building Resilience: The repeated practice of successfully grounding yourself builds confidence and resilience. You learn that even in challenging moments, you have the capacity to bring yourself back to safety and presence.

Enhanced Connection to Others and the World

When you are disconnected, it impacts your ability to engage authentically with others and your environment. Grounding can re-establish these vital connections.

- Present in Relationships: Being grounded allows you to be fully present in your interactions, leading to more meaningful connections and better communication.

- Appreciating the Everyday: It can help you to notice and appreciate the simple realities of everyday life, fostering a sense of gratitude and presence that may have been diminished.

Grounding techniques are not a magic cure, but they are invaluable tools for anyone who experiences moments of disconnection from reality. By understanding your triggers, practicing consistently, and tailoring your approach, you can harness the power of grounding to anchor yourself firmly in the present, creating a more stable and connected existence.

THE DPDR EXIT PLAN: WARNING: Your Brain Is Stuck In “Safety Mode”

FAQs

What are tactile anchors in the context of re-integrating reality?

Tactile anchors are physical objects or sensations used to help individuals reconnect with their immediate environment and reality. They provide sensory input through touch, which can ground a person experiencing dissociation, anxiety, or disorientation.

How do tactile anchors help in mental health or therapy?

Tactile anchors help by redirecting attention to the present moment through physical sensations. This can reduce feelings of detachment or overwhelm, improve focus, and support emotional regulation during therapy or stressful situations.

What are some common examples of tactile anchors?

Common tactile anchors include stress balls, textured fabrics, smooth stones, or any small object that can be held and felt. Some people also use activities like running fingers over a textured surface or holding ice cubes to create a strong sensory connection.

Who can benefit from using tactile anchors?

Individuals experiencing dissociation, anxiety, PTSD, or other mental health challenges may benefit from tactile anchors. They are also useful for anyone needing to ground themselves during moments of stress or distraction.

Can tactile anchors be used outside of therapy sessions?

Yes, tactile anchors can be used anytime and anywhere to help maintain or regain a sense of reality. They are practical tools for daily life, especially in situations that trigger stress or dissociation.