You are standing in a familiar room, perhaps your living room or office. Yet, something feels subtly, unsettlingly off. The colors seem flatter, the sounds muted, and the world alrededor you resembles a stage set rather than a lived reality. Or perhaps you look at your hands, and they feel alien, detached from you, as if observing someone else’s extremities. These are glimpses into the disorienting experiences of derealization and depersonalization, two dissociative phenomena that, while often frightening, are increasingly understood through the lens of neuroscience. This article will guide you through the intricate neural mechanisms underlying these experiences, helping you to comprehend why your perception can sometimes become so profoundly distorted.

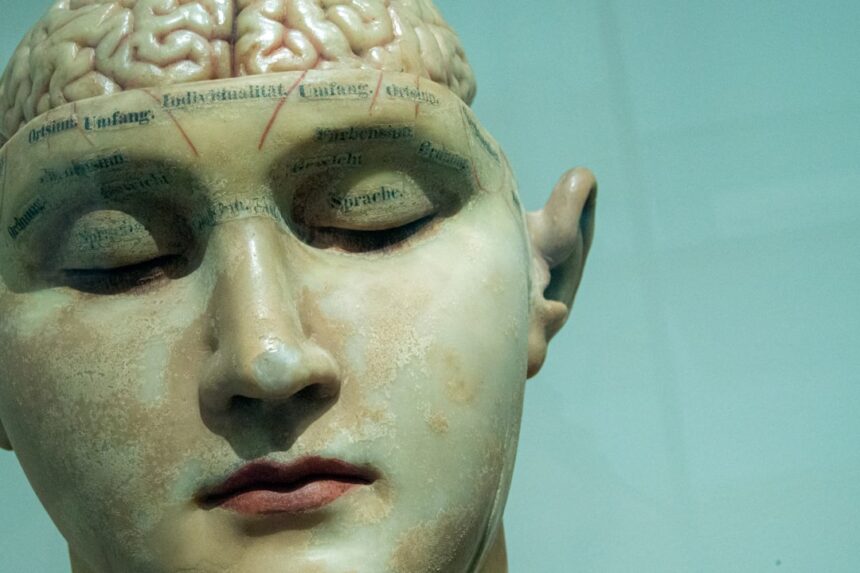

Before delving into the neuroscience, it’s crucial to understand what derealization and depersonalization truly entail. These aren’t simply feelings of being “stressed out” or “out of it”; they represent distinct alterations in your subjective experience of reality and self.

Derealization (DR)

Imagine your perception of reality as a vibrant, high-definition movie. When you experience derealization, it’s akin to that movie suddenly becoming a grainy, black-and-white film, or even a picture in a picture book.

- External World Alteration: The hallmark of derealization is a sense of unreality about the external world. You might perceive objects as flat, dull, distorted in size or shape, or even cartoon-like.

- Sensory Distortions: Auditory and visual processing can be affected. Sounds might seem distant or muffled, and colors might appear muted or bleached out.

- Emotional Detachment: While you can intellectually recognize that you are in a real place, the emotional connection to that place or the people within it feels severed. The world loses its emotional resonance.

- “Dream-like” or “Foggy” Quality: Many report that their surroundings feel dream-like, as if they are observing the world through a thick pane of glass or a veil.

Depersonalization (DP)

If derealization is the world becoming unreal, depersonalization is you becoming unreal. It’s like being the protagonist in a movie about your own life, but watching it from the director’s chair rather than experiencing it firsthand.

- Self-Detachment: The core feature of depersonalization is a feeling of detachment from your own body, thoughts, feelings, or actions. You might feel like an observer of your own life, rather than an active participant.

- Bodily Alienation: Your body might feel foreign, inanimate, or not truly yours. You might struggle to recognize yourself in the mirror, or your limbs might feel disconnected.

- Emotional Numbness: You may experience a profound inability to feel emotions, even during situations that would typically evoke strong feelings. This is distinct from depression, where emotions are present but negative.

- Loss of Agency: Actions might feel automatic or robotic, as if you are merely going through the motions without conscious control or intention.

For those interested in understanding the complex phenomena of derealization and depersonalization, a related article that delves into the neuroscience behind these experiences can be found at Unplugged Psych. This resource provides valuable insights into how these dissociative states are linked to brain function and emotional regulation, shedding light on the underlying mechanisms that contribute to the feeling of detachment from reality and oneself.

The Neurobiological Foundations: A Disconnect in Perception

At the heart of both derealization and depersonalization lies a complex interplay of neural circuits. While the exact mechanisms are still being unraveled, current research points to dysregulation in brain regions crucial for self-awareness, emotional processing, and sensory integration.

The Salience Network: A Faulty Alarm System

Imagine your brain has a sophisticated internal alarm system that alerts you to important or salient events in your environment and within yourself. This is, in essence, the salience network.

- Anterior Insula Cortex (AIC): The AIC is a central hub of the salience network. It integrates sensory, emotional, and cognitive information, determining what is relevant and what isn’t. In DP/DR, there’s evidence of reduced activity in the AIC, particularly during emotional processing. This might explain the emotional numbness; if the “alarm” for important emotional signals is muted, you feel less connected to your feelings.

- Dorsal Anterior Cingulate Cortex (dACC): Working in conjunction with the AIC, the dACC is involved in monitoring conflicts and adjusting behavior. Dysregulation here might contribute to the feeling of cognitive distortion or the sense that something is “wrong” without being able to pinpoint it.

- Impaired Integration: It’s hypothesized that the salience network in individuals with DP/DR is less effective at integrating internal (proprioceptive, emotional) and external (sensory) information. This leads to a fragmented sense of self and reality.

The Default Mode Network (DMN): Overthinking the Self

The DMN is a network of brain regions that is most active when you are not focused on a specific external task – when you are daydreaming, contemplating the future, or reflecting on yourself. It’s heavily involved in self-referential thought and autobiographical memory.

- Medial Prefrontal Cortex (mPFC): A key component of the DMN, the mPFC is crucial for self-processing, introspection, and understanding others’ mental states. In DP/DR, there might be altered connectivity or activity within the mPFC, contributing to the feeling of detachment from one’s own thoughts and feelings.

- Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC): Another core DMN region, the PCC is involved in self-reflection and retrieving episodic memories. Dysfunction here could contribute to the sense of a fragmented personal history or a feeling of being disconnected from one’s past self.

- Excessive Introspection: Some theories suggest that an overactive or dysregulated DMN in DP/DR can lead to excessive self-monitoring and unproductive rumination, further exacerbating the feeling of detachment from the automatic, lived experience. You become too aware of the process of being you, rather than simply being.

The Role of Emotion Regulation and Threat Response

Both DP and DR often emerge in the context of stress, trauma, or anxiety. This suggests a strong link to your brain’s fear and emotion regulation systems.

The Amygdala: Muted Fear

The amygdala is your brain’s alarm bell for fear and threat. It’s responsible for generating and processing emotional responses, especially those related to survival.

- Hypoactivity in DP/DR: Counterintuitively, studies have shown that individuals experiencing DP/DR often exhibit reduced activity in the amygdala, particularly in response to emotional stimuli. This doesn’t mean they don’t perceive threat; rather, their emotional response to it is blunted. This could be a protective mechanism: faced with overwhelming threat, the brain “switches off” the emotional component to reduce distress, leading to emotional numbness.

- Connectivity with Prefrontal Cortex: The amygdala typically interacts extensively with the prefrontal cortex (PFC), which helps regulate emotional responses. Dysfunctional connectivity here might impair your ability to integrate emotional information with conscious thought, further contributing to the sense of unreality.

The Prefrontal Cortex (PFC): Over-Regulation and Disconnect

The PFC is the executive control center of your brain, involved in planning, decision-making, and, crucially, emotion regulation.

- Hyperactivity in Lateral PFC (lPFC): Some research indicates increased activity in the lPFC in DP/DR. This region is involved in reappraisal and suppression of emotional responses. This increased activity might represent an attempt by your brain to consciously suppress or control overwhelming emotional input, thus creating a state of emotional detachment or “switching off.”

- Disrupted Top-Down Control: It’s thought that the PFC normally exerts top-down control over subcortical emotional areas like the amygdala. In DP/DR, this control might become excessively strong or dysfunctional, leading to an over-suppression of emotional experience and a resultant feeling of emptiness or unreality.

Sensory Processing and Perceptual Integration

Your perception of reality is a seamless integration of sensory inputs. When this integration goes awry, the world can feel alien.

The Temporoparietal Junction (TPJ): The Seat of the Self

The TPJ is a critical region involved in integrating sensory information from different modalities (sight, sound, touch) and in self-other distinction. It plays a significant role in body ownership and spatial awareness.

- Distorted Body Schema: Dysfunction in the TPJ can lead to disruptions in your body schema – your internal representation of your own body. This could explain why your limbs feel alien or why you might struggle to recognize yourself.

- Out-of-Body Sensations: In more severe cases, TPJ dysfunction is linked to out-of-body experiences, where you feel like you are observing your body from an external vantage point. This is a profound form of depersonalization.

- Impaired Global Integration: The TPJ is a convergence zone. If its ability to integrate diverse sensory streams is compromised, the holistic, unified perception of reality and self can fragment, leading to the disjointed experiences of DP/DR.

Thalamocortical Dysregulation: The Brain’s Filter

The thalamus acts as a major relay station, filtering and transmitting sensory information from the body to various parts of the cerebral cortex.

- Altered Sensory Gating: It’s hypothesized that in DP/DR, there might be altered sensory gating mechanisms within the thalamus or its connections to the cortex. This could mean that sensory information is either over-filtered (leading to a dull, muted world) or improperly processed, contributing to the feeling of unreality.

- Disrupted Oscillations: The brain communicates through electrical oscillations (brainwaves). Studies suggest that abnormal oscillatory activity, particularly in gamma and alpha bands, might be present in DP/DR. These oscillations are crucial for binding sensory features into coherent percepts. Disruption could result in fragmented or distorted perceptions. For example, if the brain’s synchronicity, like an orchestra playing in perfect harmony, falters, the resulting music (your reality) sounds discordant.

The intriguing phenomena of derealization and depersonalization have long captivated researchers in the field of neuroscience, as they delve into the complexities of human perception and self-awareness. A related article that explores these topics in depth can be found at Unplugged Psych, where the mechanisms behind these experiences are examined alongside potential therapeutic approaches. Understanding how the brain processes reality and self-identity is crucial for developing effective interventions for those affected by these dissociative states.

Implications for Understanding and Treatment

| Aspect | Neuroscientific Findings | Implications for Derealization and Depersonalization | Relevant Brain Regions | Measurement/Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altered Sensory Integration | Disrupted connectivity between sensory cortices and limbic system | Leads to altered perception of self and environment, causing feelings of unreality | Temporal cortex, Insula, Thalamus | fMRI connectivity analysis |

| Emotional Processing Deficits | Reduced activation in amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex during emotional stimuli | Blunted emotional responses contribute to depersonalization symptoms | Amygdala, Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) | fMRI BOLD response to emotional tasks |

| Altered Self-Referential Processing | Decreased activity in medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) | Impaired self-awareness and self-recognition | Medial prefrontal cortex | Resting-state fMRI, PET scans |

| Increased Default Mode Network (DMN) Activity | Hyperactivity in DMN regions during rest | May contribute to dissociative experiences by excessive internal focus | Posterior cingulate cortex, Precuneus, mPFC | Resting-state fMRI connectivity |

| Neurochemical Imbalance | Altered glutamate and GABA neurotransmission | Disrupted excitatory/inhibitory balance linked to symptoms | Various cortical and subcortical areas | MR spectroscopy |

| Autonomic Nervous System Dysregulation | Abnormal heart rate variability and sympathetic activity | May underlie physiological sensations of detachment | Brainstem, Hypothalamus | Heart rate variability (HRV) metrics |

Understanding the neuroscience behind derealization and depersonalization is not merely an academic exercise; it has profound implications for how you, as someone experiencing these phenomena, or as a clinician assisting someone who is, approach it.

Beyond Psychosomatic: A Biological Basis

For a long time, DP/DR was often dismissed as “just stress” or “all in your head.” Neuroscientific research firmly refutes this. While stress and psychological factors are significant triggers, the experiences themselves are rooted in demonstrable neurobiological alterations. This validation is often a crucial first step for individuals struggling with these symptoms, reaffirming that what they are experiencing is real and not simply a figment of their imagination.

Targeted Therapeutic Approaches

Knowledge of the underlying neural circuits opens doors for more targeted interventions.

- Pharmacological Interventions: While direct pharmaceutical cures for DP/DR are not yet established, understanding neurotransmitter imbalances (e.g., in glutamate, GABA, serotonin, dopamine systems, which influence the identified neural networks) could lead to the development of more specific medications. Currently, treatments often focus on underlying anxiety or depression.

- Neurofeedback and Neuromodulation: Techniques like neurofeedback, which train you to self-regulate brain activity, or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which can modulate activity in specific brain regions, hold promise. If specific brain regions or networks are under or overactive, these methods could potentially rebalance them.

- Psychotherapeutic Interventions: Therapies such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) can help you manage the anxiety, panic, and distress associated with DP/DR. By understanding the neural basis, therapists can help you contextualize these experiences, reduce catastrophic interpretations, and learn coping mechanisms that might implicitly recalibrate brain activity. For example, grounding techniques help you re-engage your sensory systems and bring online the very networks that process reality and self-perception.

In conclusion, experiencing derealization and depersonalization can be profoundly disorienting and frightening. However, by exploring the intricate neural underpinnings – the salience network’s faulty alarms, the default mode network’s over-introspection, the amygdala’s muted fear response, the PFC’s over-regulation, and the TPJ’s disrupted integration – you can begin to demystify these enigmatic states. You are not “going crazy”; your brain, in response to various stressors, is operating in a way that temporarily distorts your fundamental sense of reality and self. This scientific understanding provides not only an explanation but also a pathway toward coping, intervention, and ultimately, a more integrated perception of yourself and the world you inhabit.

THE DPDR EXIT PLAN: WARNING: Your Brain Is Stuck In “Safety Mode”

FAQs

What is derealization and depersonalization?

Derealization is a dissociative symptom where the external world feels unreal or distorted, while depersonalization involves a sense of detachment from oneself, as if observing one’s thoughts or body from outside. Both are common experiences in various mental health conditions.

What brain areas are involved in derealization and depersonalization?

Neuroscientific research points to altered activity in the prefrontal cortex, limbic system (including the amygdala), and temporoparietal junction. These regions are associated with emotional processing, self-awareness, and sensory integration, which are disrupted during episodes.

How do neurotransmitters affect these dissociative experiences?

Neurotransmitters such as serotonin, glutamate, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) play roles in regulating mood, perception, and anxiety. Imbalances or dysregulation in these chemicals can contribute to the onset of derealization and depersonalization symptoms.

Can neuroimaging help diagnose derealization and depersonalization?

While neuroimaging techniques like fMRI and PET scans have identified brain activity patterns linked to these conditions, they are not currently used as standalone diagnostic tools. Diagnosis primarily relies on clinical assessment and patient history.

Are there effective treatments targeting the neuroscience of these conditions?

Treatment often includes psychotherapy, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and sometimes pharmacotherapy targeting neurotransmitter systems. Emerging research is exploring neuromodulation techniques, but more studies are needed to establish their efficacy.