Reclaiming Your Present: Orienting Exercises for Dissociation Recovery

If you are reading this, you may be navigating the complex terrain of dissociation. This can manifest in various ways, from feeling detached from yourself or your surroundings to experiencing gaps in memory or a sense of unreality. Dissociation, often a survival mechanism in response to overwhelming experiences, can leave you feeling like a ship adrift without an anchor, disconnected from the steady shores of the present moment. Reclaiming your present is not about erasing your past, but about building a bridge back to the here and now, making it a safe and navigable space for you. This article will explore a suite of orienting exercises designed to help you ground yourself, reconnect with your senses, and rebuild your relationship with reality.

Dissociation is not a monolithic experience. It’s a spectrum of phenomena that represent a disconnection between consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, and behavior. Think of it as a finely tuned dimmer switch on your internal awareness, which, when turned down too low, can leave you feeling distant, unreal, or even absent from your own life. This disconnection is not a failing; it is your mind’s ingenious, albeit painful, way of coping with trauma or extreme stress.

The Spectrum of Dissociative Experiences

- Depersonalization: This is the feeling of being detached from your own body, thoughts, feelings, or sensations. You might feel like an observer of your own life, watching yourself from the outside, or as if you are a robot with no real agency. It’s like watching a movie of your life where you are the main character, but you can’t quite feel the emotions of the character on screen.

- Derealization: This refers to a feeling of detachment from your surroundings. The world might appear unreal, dreamlike, fog-bound, or distorted. Objects may seem flat, colors muted, and familiar places may feel alien. It’s akin to looking at the world through a thick pane of glass, where everything is visible but not truly tangible or connected to you.

- Dissociative Amnesia: This involves the inability to recall important personal information, especially related to traumatic experiences. It can range from forgetting specific events to a complete inability to remember one’s own identity, leading to periods of confusion and disorientation. This is like having missing chapters in your personal autobiography, leaving you with gaps in your narrative.

- Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID): Previously known as Multiple Personality Disorder, DID is characterized by the presence of two or more distinct personality states that recurrently take control of the individual’s behavior, accompanied by memory gaps beyond ordinary forgetfulness. This is a more complex manifestation where distinct parts of the self, or “alters,” emerge with their own names, histories, and characteristics, often as a way to compartmentalize overwhelming experiences.

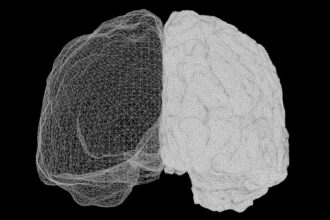

The Neurological Underpinnings of Dissociation

From a neurobiological perspective, dissociation is understood as a disruption in the brain’s ability to integrate information and maintain a coherent sense of self. This can involve altered activity in brain regions responsible for memory consolidation (hippocampus), emotional processing (amygdala), and self-awareness (prefrontal cortex). When the brain is overwhelmed, it can fragment its processing to manage the distress. This fragmentation, while a protective mechanism, can lead to the subjective experiences of dissociation.

For those seeking effective strategies to aid in dissociation recovery, a valuable resource can be found in the article on orienting exercises available at Unplugged Psychology. These exercises are designed to help individuals reconnect with their surroundings and enhance their sense of safety and presence. To explore these techniques further, you can read the article here: Unplugged Psychology.

Grounding Yourself: Anchors in the Present

When you feel yourself drifting, grounding exercises act as your anchors, pulling you back to the solid ground of the present moment. They are about engaging your senses and your physical self to remind you that you are here, now, in this body, in this space. The key is to actively and deliberately bring your awareness to what is happening in the immediate environment and within your own body.

Sensory Grounding Techniques

These exercises involve intentionally focusing on your sensory input to bring you back to the physical world.

The 5-4-3-2-1 Method

This is a widely recognized and effective grounding technique. You systematically engage your senses to identify aspects of your immediate environment.

- Identify 5 things you can see: Look around you. What colors do you notice? What shapes? What textures? Focus on specific details. For example, “I see the blue of the pen on the table,” or “I see the grain of the wood in the desk.”

- Identify 4 things you can touch: What can you feel against your skin? The fabric of your clothes, the chair beneath you, the cool air on your face, the texture of your own hands. You can deliberately touch objects: the smooth surface of a table, the fuzzy texture of a throw pillow, the cool metal of a doorknob.

- Identify 3 things you can hear: Listen to the sounds around you, both near and far. The hum of a refrigerator, the distant traffic, a clock ticking, your own breath. Try to distinguish different layers of sound.

- Identify 2 things you can smell: What aromas are present? The scent of soap, food, flowers, or even just the neutral smell of the air. If there are no distinct smells, you can inhale deeply and notice the faint scent of your own skin or clothing. Bringing a scented item, like a lavender sachet or a piece of citrus peel, can be helpful.

- Identify 1 thing you can taste: If you have something to eat or drink, focus on the taste. If not, you can focus on the natural taste in your mouth, the lingering taste of toothpaste, or even the subtle sensation of your tongue against the roof of your mouth.

Body Scan Meditation

This exercise involves bringing soft, non-judgmental attention to different parts of your body.

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation: Systematically tense and then release different muscle groups, starting from your toes and moving up to your head. Notice the sensation of tension and then the wave of release. This helps you reconnect with the physical sensations in your body.

- Awareness of Physical Sensations: Simply bring your attention to different parts of your body without trying to change anything. Feel the weight of your body supported by the chair or bed. Notice the temperature of your skin, the rhythm of your breath, or any areas of tightness or comfort.

Physical Grounding Techniques

These exercises involve physically interacting with your environment to create a sense of stability.

- Foot Grounding: Plant your feet firmly on the ground. Wiggle your toes. Feel the pressure of the floor beneath your soles. Imagine roots extending from your feet into the earth, drawing stability and energy upward.

- Hand Grounding: Hold an object in your hands and focus on its texture, temperature, and weight. This could be a smooth stone, a soft piece of fabric, or even the keys in your pocket.

Engaging Your Mind: Exercises for Present Moment Awareness

While sensory exercises bring you back to your physical reality, mental exercises focus on directing and reorienting your attention to the present. When dissociation occurs, your mind may be racing or shut down, disconnected from the immediate flow of time. These techniques help to bring your cognitive awareness back to the here and now.

Cognitive Reorientation

This involves actively bringing your attention to facts of the present moment.

Fact-Checking Your Environment

This is similar to the 5-4-3-2-1 method but focuses on concrete facts rather than solely sensory input.

- What is your name? Say it out loud.

- Where are you right now? Be specific. “I am in my living room.” “I am at my desk in my office.”

- What time is it? Look at a clock or watch.

- What day of the week is it?

- What month is it?

- What year is it?

- Who are the people around you (if any)? Name them if you know them.

- What is the general purpose of this location? “This is a place where I relax.” “This is a place where I work.”

Describing Your Surroundings Objectively

This exercise requires you to describe your environment in a neutral, factual way, as if you were reporting on it for a news broadcast.

- Focus on observable, verifiable details: “The walls are painted a light beige.” “There is a rectangular table with four chairs.” “The window is open, allowing a slight breeze.” Avoid interpretation or emotional commentary. This helps to break the cycle of distorted perceptions often associated with derealization.

Mindful Observation

Mindfulness is the practice of paying attention to the present moment without judgment. When adapted for dissociation recovery, it becomes a tool for gently re-engaging with reality.

- Observing an Object: Choose a simple object, like a pen, a leaf, or a piece of fruit. Observe it in detail. Notice its color, shape, texture, and any subtle variations. Imagine you are seeing it for the first time. This trains your brain to focus on singular, observable phenomena.

- Observing Your Breath: Your breath is a constant, tangible anchor to the present. Without trying to change it, simply notice the sensation of your breath as it enters and leaves your body. Feel the rise and fall of your chest or abdomen. This is a fundamental mindfulness practice that can be used whenever you feel yourself dissociating.

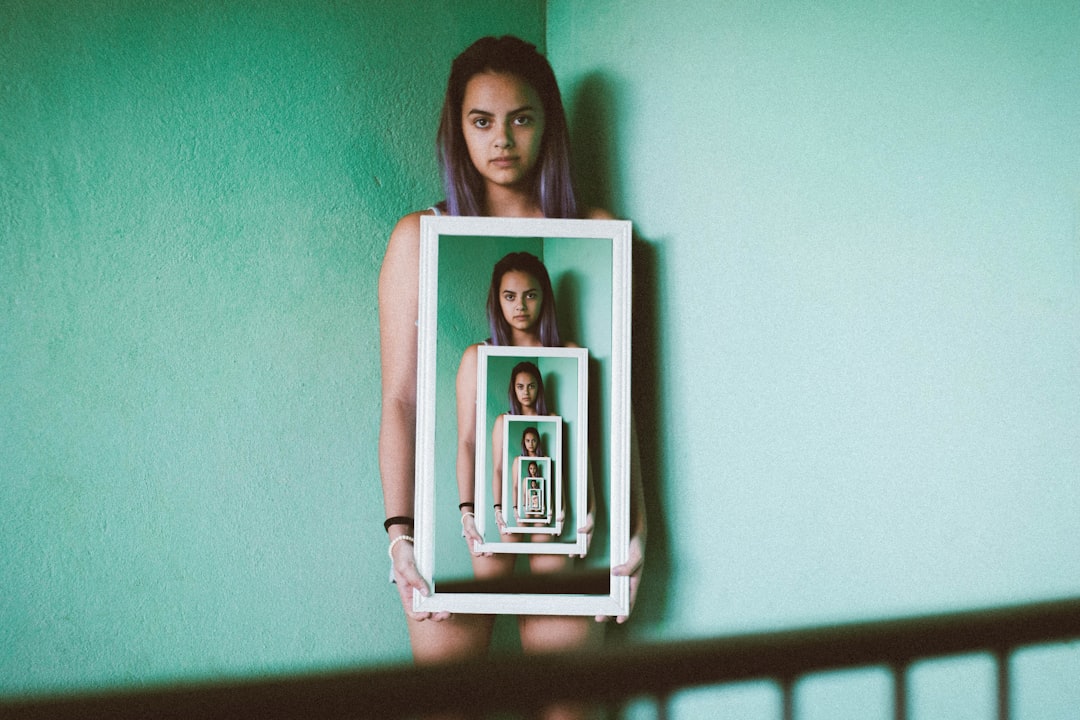

Connecting with Your Body: Embodiment Practices

Dissociation often involves a feeling of disconnection from one’s own physical self. Embodiment practices aim to re-establish this connection, fostering a sense of ownership and presence in your body. This is about recognizing your body not as a foreign entity, but as your home, your vessel for experiencing life.

Movement and Physical Activity

Gentle, mindful movement can be a powerful way to reconnect with your physical sensations.

- Stretching: Perform slow, deliberate stretches, paying attention to the sensations in your muscles and joints. Notice where you feel tension and where you feel release. Focus on the feeling of your limbs extending and contracting.

- Walking: When you walk, pay attention to the physical sensations of your feet making contact with the ground, the movement of your legs, and the rhythm of your breath. Engage your senses as you walk – notice the sights, sounds, and smells around you.

- Simple Exercises: Gentle exercises like yoga, Tai Chi, or even just making small, deliberate movements can help you feel more present in your body. The key is to focus on the physical sensations rather than pushing yourself physically.

Biofeedback Techniques (Self-Administered)

While formal biofeedback requires equipment, you can practice similar principles yourself.

- Monitoring Your Pulse: Find your pulse in your wrist or neck. Focus on the rhythm and strength of your heartbeat. This is a direct, undeniable sign of being alive and present.

- Noticing Your Body Temperature: Place your hands on your arms or legs and notice the temperature of your skin. You can also hold a warm or cool object and notice how it affects your sensation.

For those seeking effective strategies in dissociation recovery, engaging in orienting exercises can be incredibly beneficial. These exercises help individuals reconnect with their surroundings and enhance their sense of presence. To explore more about this topic, you can read a related article that delves into various techniques and practices designed to aid in this journey. Discover valuable insights and guidance by visiting this resource that focuses on mental health and wellness.

Re-establishing Routine and Predictability

| Exercise | Description | Duration | Frequency | Benefits | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-4-3-2-1 Grounding | Identify 5 things you see, 4 you can touch, 3 you hear, 2 you smell, 1 you taste | 5 minutes | 3-5 times daily | Enhances present moment awareness and reduces dissociative symptoms | Can be done anywhere; useful during dissociative episodes |

| Body Scan | Focus attention sequentially on different parts of the body to increase bodily awareness | 10-15 minutes | Daily | Improves mind-body connection and reduces feelings of detachment | Best done in a quiet, comfortable environment |

| Orientation to Time and Place | Verbalize current date, time, location, and situation | 2-3 minutes | As needed, especially during episodes | Reinforces reality testing and reduces confusion | Can be guided by a therapist or self-administered |

| Deep Breathing | Slow, controlled breaths focusing on inhalation and exhalation | 5-10 minutes | 2-3 times daily or during stress | Calms nervous system and anchors attention to the body | Combine with grounding for enhanced effect |

| Object Focus | Hold and describe an object in detail to engage senses and attention | 3-5 minutes | As needed | Improves sensory engagement and reduces dissociative detachment | Choose objects with comforting or neutral associations |

When dissociation makes time feel fluid and unreliable, establishing predictable routines can provide a much-needed sense of stability and order. Routines act as the consistent currents that keep your ship from drifting aimlessly. They are the dependable markers that help you track the passage of time and your place within it.

Daily Structure and Consistency

- Scheduled Mealtimes: Eating at regular intervals helps to regulate your body’s internal clock and provides concrete points in the day.

- Regular Sleep Schedule: Aim for consistent times for going to bed and waking up. This promotes physical and mental restoration and anchors your days and nights.

- Planned Activities: Incorporate a mix of enjoyable and functional activities into your day. This could include hobbies, social interactions, or essential tasks. Knowing what to expect can reduce anxiety and the tendency to dissociate.

Creating Rituals and Milestones

Rituals, whether simple or elaborate, imbue the passage of time with meaning and structure.

- Morning Ritual: This could be anything from making a cup of tea and reading a few pages of a book to journaling or practicing a short meditation. The key is consistency.

- Evening Wind-Down Routine: This helps signal to your body and mind that it’s time to prepare for rest. It might involve taking a warm bath, listening to calming music, or reading.

- Marking Transitions: Acknowledge and mentally acknowledge the transitions between different parts of your day. For example, “Now the workday is over, and I am entering my evening time.”

Integrating the Present: A Path Toward Recovery

Reclaiming your present is not a one-time event but an ongoing process. It requires patience, self-compassion, and consistent practice. These exercises are tools in your recovery toolkit, designed to empower you to navigate the challenges of dissociation and live a more grounded, connected life. Remember that seeking professional support from a therapist specializing in trauma and dissociation is crucial for a comprehensive recovery journey.

The Role of Professional Support

- Therapeutic Interventions: Therapists can provide psychoeducation about dissociation, help you process underlying trauma, and guide you through specialized techniques like Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) or Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT).

- Creating a Safe Space: A therapist can offer a safe, non-judgmental environment where you can explore your experiences and develop coping mechanisms.

Self-Compassion and Persistence

- Acknowledge Your Progress: Celebrate small victories. Every time you successfully ground yourself or bring your awareness back to the present, you are building resilience.

- Be Patient with Yourself: Recovery is not linear. There will be times when you feel more dissociated. This is normal. Gently return to your grounding and orienting exercises without self-criticism.

- View Dissociation as a Process: Understand that dissociation developed as a coping mechanism. Reclaiming your present is about teaching your system that it is safe to be present now, even if the past was overwhelming.

By consistently engaging with these orienting exercises, you are actively weaving yourself back into the fabric of the present moment. You are learning to navigate the currents of your experience with greater awareness and stability, transforming from a ship adrift to a vessel skillfully charting its own course.

WARNING: Your “Peace” Is Actually A Trauma Response

FAQs

What are orienting exercises in the context of dissociation recovery?

Orienting exercises are grounding techniques designed to help individuals reconnect with the present moment and their immediate environment. They often involve sensory awareness, such as noticing sights, sounds, smells, or physical sensations, to reduce feelings of dissociation.

How do orienting exercises help in managing dissociation?

These exercises help by redirecting attention away from dissociative experiences and toward the here and now. This can improve awareness, reduce anxiety, and increase a sense of safety and control during episodes of dissociation.

Can orienting exercises be used independently, or should they be guided by a therapist?

While some orienting exercises can be practiced independently once learned, it is generally recommended to start under the guidance of a mental health professional. A therapist can tailor exercises to individual needs and ensure they are used safely and effectively.

What are some common examples of orienting exercises for dissociation recovery?

Common exercises include naming five things you can see, four things you can touch, three things you can hear, two things you can smell, and one thing you can taste. Other techniques involve deep breathing, feeling the texture of an object, or focusing on the sensation of feet on the ground.

How often should orienting exercises be practiced for effective dissociation recovery?

The frequency varies depending on individual needs and treatment plans. Some people may benefit from practicing these exercises daily to build grounding skills, while others may use them primarily during or immediately after dissociative episodes. Consistency and regular practice can enhance their effectiveness.